Paediatric fluid management

There's a unique feeling when, after intubating and establishing your maintenance anaesthesia, slipping in a second cannula and picking up the anaesthetic chart, you sit down and realise that you left the fluid open and now the whole litre has gone in over eight minutes.

Whoops.

In the absence of severe fluid overload or cardiac failure, this is generally not an issue in the majority of adult patients, many of whom are rather profoundly dehydrated to start with and could do with a decent bit of filling to offset the vasoplegia of anaesthesia.

However kids will not be so understanding of your inattention, so you need to have a slightly more diligent and scientific approach to their fluid management, especially if they're critically unwell.

There are only three fluids

When it comes to infusing liquids into a child's venous system, you really only have three options:

- Isotonic crystalloid

- Hypertonic crystalloid

- Blood products

That's it.

Each has their own indications and pitfalls, which we'll discuss, but if you're about to plumb in a colloid or something other than these three, have another think first.

Resus vs Maintenance

There are two forms of 'giving fluid' to a patient.

You can give resuscitation fluid, or you can give maintenance fluid.

- Resuscitation fluid is to restore a perfusing circulating volume and to fix pre-existing dehydration

- Maintenance fluid is to replace ongoing fluid loss in a euvolaemic patient

Decide which one you're doing, and commit to it.

Resuscitation

- 10 mg/kg over 10 - 15 minutes

The key is to give a bolus, and then see if it has done anything useful before giving another.

If you've given four or five boluses and aren't getting anywhere, it's time to try something else.

What are the signs that your resuscitation fluid has worked?

- Heart rate drops

- Blood pressure increases

- Child is more alert

- Urine output increases

You're aiming for normalisation of physiological parameters, and ideally a urine output of at least 2 ml/kg/hour.

Blood pressure dropping is a very late sign of hypovolaemia in kids.

Blood needs blood

If you're looking at a child that needs fluid replacement because they've lost a lot of blood, then it should hopefully come as no surprise that the optimal fluid to replace it with is blood.

- 10 ml/kg warm packed red cells

- 10 ml/kg warm fresh frozen plasma

- 10 ml/kg cryoprecipitate if you've got it

- Give platelets after every 20 ml/kg of packed red cells

- In kids over 15 kg use an adult pack of platelets, and give 10-15 ml/kg if they're less than 15 kg

The exact volumes and order of infusion varies depending on which protocol you read, so use the one for your institution.

Oh, and don't forget to think about the other bad things associated with major haemorrhage:

- Hyperfibrinolysis

- Acidosis

- Hypothermia

- Coagulopathy

- Hypocalcaemia

For now we'll leave the full management of paediatric major haemorrhage to another post.

How dehydrated is this child?

This is generally assessed using the three-category scale of mild, moderate and severe.

Mild

- 5% bodyweight drop

- Normal fontanelle, eyes and skin turgor

- Moist mucous membranes

- Normal pulse and respiratory pattern

- Urine output 1 - 2 ml/kg/hour

Moderate

- 10% bodyweight drop

- Sunken fontanelle and eyes

- Decreased skin turgor

- Increased pulse and respiratory rate

- Urine output 0.5 - 1 ml/kg/hour

Severe

- 15% bodyweight drop

- Markedly sunken fontanelle and eyes

- Very decreased skin turgor

- Rapid pulse and deep sighing respiratory pattern

- Urine output less than 0.5 ml/kg/hour

A 10kg child who is 5% dehydrated will be 500ml deplete.

Maintenance fluids

If we assume that your patient has been adequately resuscitated, but is now unable to manage their own fluid balance with oral fluids, you might need to consider some maintenance therapy.

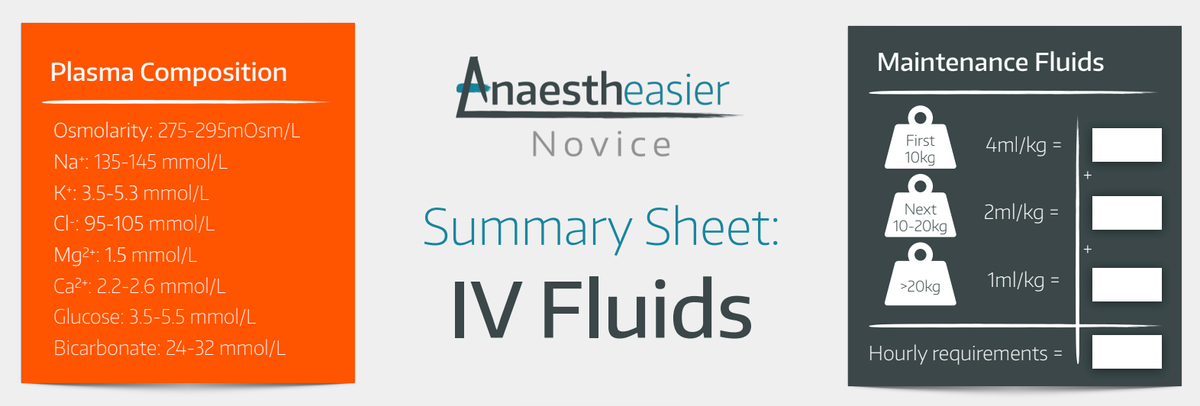

4-2-1

This is the standard maintenance fluid therapy for children, and an FRCA exam favourite.

- For the first 10 kg of body weight, give 4 ml/kg/hour

- For the next 10 kg, give 2ml/kg/hour

- For remaining weight, give 1ml/kg/hour

So a 27 kg child would need 40 + 20 + 7 = 67 ml/kg/hour

Bear in mind this is specific to water requirement, and doesn't necessarily mean you're covering the bases with your electrolytes - these will need monitoring and correcting as needed.

Remember this is a baseline for a relatively well child that is nil by mouth. As soon as you add in hyperventilation or pyrexia, the requirements shoot up pretty quickly.

This is why urine output, lactate, heart rate etc should be used to guide therapy rather than blindly following an algorithm of numbers.

How do I figure out third space losses in theatre?

Yeah good question, it's not easy.

The following is a reasonable estimate:

- 1-2 ml/kg/hour for superficial operations

- 4-7 ml/kg/hour for thoracotomy

- 5-10 ml/kg/hour for abdominal surgery

Most kids over 1 month old will hold a steady blood sugar in theatre without needing extra dextrose.

Kids at risk of hypoglycaemia:

- TPN

- <3rd centile bodyweight

- Lots of regional anaesthesia

- Operation longer than 3 hours

Hypertonic saline

The classic indication for using hypertonic fluid is as osmotherapy to reduce intracranial pressure.

- Hypertonic saline lowers the water potential of the blood

- This generates a water potential gradient from cerebral tissue to the plasma

- Water is drawn out of the brain, reducing the volume of the brain tissue

- This reduces the pressure in the head

It is not a definitive treatment, rather a temporising measure to allow you to get the child to a neurosurgeon.

- The other common situation is treatment of cerebral oedema in hyponatraemic patients in diabetic ketoacidosis

This is almost always enough to give a meaningful clinical response, and will usually raise the serum sodium concentration by around 2 mmol/L.

I have a child with sepsis who is not responding to fluids, what should I do?

Firstly, well done for recognising that you have a septic child with fluid-refractory shock.

Secondly - call for help.

Hopefully your consultant is already at least vaguely aware of this patient. Now it's time to get your nearest paediatric ICU involved, even if only for advice.

If you have given up to 60 ml/kg of balanced isotonic fluid and the child is still demonstrating signs of shock, you need to think about vasoactive drugs.

- Ideally gain central access, but you can give peripherally if needed

- Intubating early is a good plan as they're likely to decompensate further

- It is worth continuing fluid therapy as well if there was some response albeit not enough

Peripheral vasoactives

- If the child has warm hands and a wide pulse pressure, think about noradrenaline 0.1 mcg/kg/min up to 1 mcg/kg/min

- If the child has cold hands and a narrow pulse pressure, consider adrenaline 0.1 mcg/kg/min up to 1 mcg/kg/min

If the pressors aren't working

- Rule out other reasons why the child is in shock - tamponade, pneumothorax, intracranial event

- Consider a bolus of IV hydrocortisone 2 mg/kg

We cannot stress this enough - this is not anaesthetic registrar in a DGH level stuff, this is consultant anaesthetist talking to PICU level stuff - call for help early.

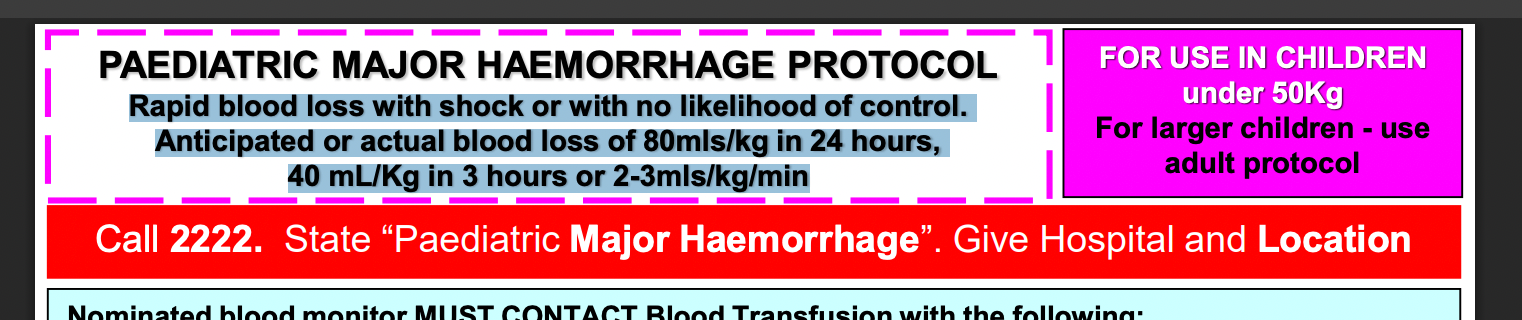

I'm not sure if this is minor bleeding or major haemorrhage?

Definition of major haemorrhage in kids:

- Rapid blood loss with shock or with no likelihood of control any time soon

- Anticipated or actual blood loss of 80mls/kg in 24 hours

- or 40 mL/Kg in 3 hours

- or 2-3mls/kg/min

I have a cold shocked patient in DKA, how should I manage their fluids?

Carefully. And call PICU early.

Volume assessment is tricky as they're profoundly dehydrated, vasoconstricted, acidotic and hyperventilating.

- Use urine output and lactate as your measures of whether shock is improving or not

- 10 ml/kg bolus of 0.9% sodium chloride or Plasmalyte/equivalent

- Consider a further bolus if needed

- If still shocked after 20 ml/kg then consider early use of peripheral vasoactives

If you get a drop in GCS or other neurological signs, assume this is due to cerebral oedema.

- 3 ml/kg 2.7% sodium chloride

When you're giving insulin to a patient in DKA, you need to remember that both glucose and sodium are doing the osmotic work to stop the brain from swelling.

If you drop the glucose too quickly without replacing the sodium, then you risk oedema and all of its messy consequences.

- Corrected Sodium (Na) = Plasma Na + (0.3 x (Glucose – 5.6))

If the corrected sodium drops by >5 mmol/L in 4 hours, then reduce fluid rate by 50%.

Did we mention call for senior help please?

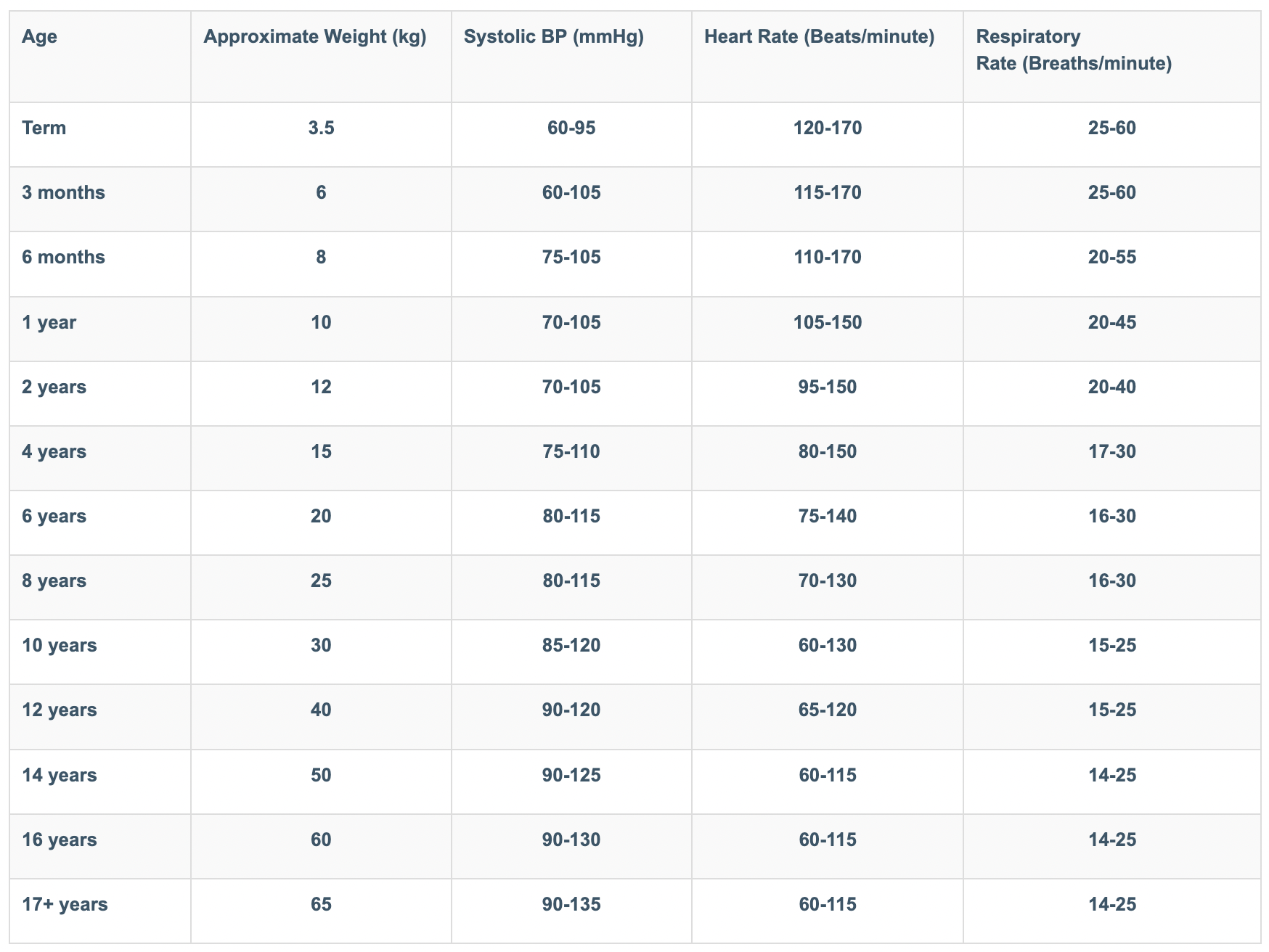

Normal physiological parameters by age

Here's a great table from the Royal Children's Hospital in Melbourne.

Remember the trend is just as important as the number. If things appear to be heading in the right direction, hold tight and keep going.

References and Further Reading

Related posts