Gas Laws

Gases are cool, especially when they make people go unconscious through incompletely understood mechanisms.

As an anaesthetist you need to understand how and why gases tend to behave in certain conditions, as this can and will impact how you use them in your clinical practice.

Arguably more importantly it gets examined frequently in the Primary FRCA, and so here we've compiled everything you could possibly hope to need to know.

Let's start with Dalton

Assuming you're not sat in a room at a temperature of 0°K, then all gas molecules will have some kinetic energy, and will therefore exert a force on anything they bump into, such as other molecules or the walls of a container.

- The force applied over a given area is pressure

More molecules, or more energy, and you get more force and thus more pressure.

Now if you have a mixture of gases, such as room air, then each constituent such as nitrogen and oxygen will exert pressures independently of one another.

- If room air is at ambient pressure of 101.3 kPa

- The nitrogens will contribute 78-ish of those kPa

- The oxygens will contribute 21-ish of those kPa

If you took the nitrogens out, the oxygens will still generate 21 kPa of pressure, and vice versa.

The partial pressure is the proportion of the overall pressure that a given gas contributes, or the pressure exerted by each component of a mixture of gases.

Now Henry

Many gases will dissolve into a fluid, such as CO2 or Oxygen into water or plasma.

It's hopefully fairly intuitive that if you apply an enormous partial pressure of a given gas above a fluid, then you'll encourage more molecules to dissolve into that fluid (kind of like a concentration gradient).

- Gas tension is expressed as the equivalent partial pressure of a gas that is in solution

- Super-technically speaking, a dissolved gas can't exert a partial pressure, because it is dissolved, however for any given tension, there will be a corresponding partial pressure required to achieve that amount of dissolved gas

- So we use them essentially interchangeably

- P = Hv x M

Where P is partial pressure of the gas, Hv is Henry’s proportionality constant (specific to gas and temperature) and M is the molar concentration of gas.

Why does my fluid warmer have an air trap?

Nice question.

When gas dissolves in liquid, the molecules are held in solution by weak intermolecular forces. At any given time, some gas molecules will have sufficient energy to break away (back into the gaseous form) while others are being dragged back into solution.

- This is a continuous dynamic equilibrium

If you heat the fluid up, and add energy to the system, you're giving more of those gas molecules more energy, so more of them will escape solution and form gas bubbles.

- This is why rising sea temperatures is bad news for CO2 levels, as warm seawater will release yet more CO2 into the atmosphere and make the whole situation worse

- It's also why putting carbonated drinks in the fridge will keep them bubbly for longer

The air trap is to prevent venous air embolism, which is more likely if your fluid is suddenly full of bubbles.

Robert Boyle

I remember this as 'Boyle is boiling', so I know it's the temperature that is kept constant.

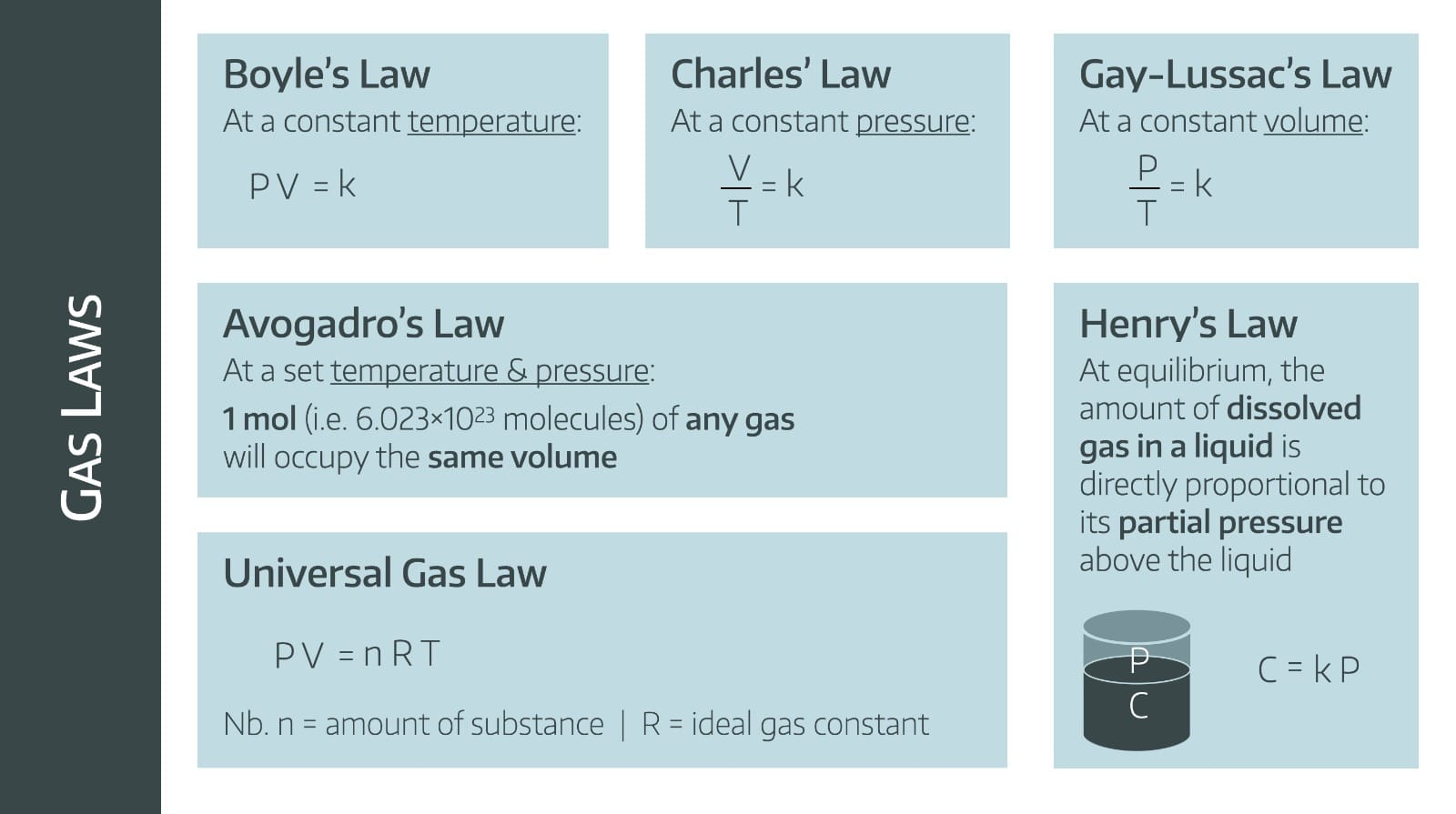

- PV = k

Where P = pressure, V = volume and k = a constant.

Alternatively you can express it as

- P1V1 = P2V2

How much oxygen is in your cylinder?

A size F cylinder has an internal volume of around 10 litres, and when full will have a pressure of 13800 kPa*.

So what volume will this occupy when released to atmospheric pressure?

- P1V1 = P2V2

- 13800 kPa x 10 L = 100 kPa x V2

- V2 = 1380 litres

*If you're thinking it should be 13700 then you're thinking of gauge pressure. For these calculations you need to use absolute pressure, and add the 100 kPa or so of atmospheric as well.

When you use up all the oxygen in the cylinder, the pressure inside the cylinder will equilibrate with atmospheric pressure, meaning there will be 10 litres of oxygen still left in the tank, so you only actually get 1370 L of usable oxygen.

Jacques Charles

He's our favourite of the lot, purely because in 1783 he flew the first ever hydrogen balloon, and personally ascended to around 3 km in altitude, which is pretty cool.

In the late 1700s curious JC was messing around with gases and noticed that when you heat them up, they expand, and when you cool them down again, they contract.

He never actually published his results, but everyone has duly credited him with the law in the spirit of good science.

Tip top.

I remember this as 'Charles in charge is always cool under pressure' so I know it's the pressure that is kept constant.

Don't ask me why.

Simply put:

- Volume/Temperature = k (a constant)

Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac

Similar theme, curious dude playing with gases, comes up with sensible suggestion.

Also a keen balloonist, reaching around 7 km altitude in 1804 (not examinable).

I remember this as ‘Gay-Lussac is a voluminous name’, therefore the volume is kept constant.

Amedeo Avogadro

In 1811, Avogadro suggested a groundbreaking idea:

At the time this groundbreaking concept didn't get the recognition it deserved (like everything in science) largely because scientists couldn't agree on what particles, atoms or molecules actually were.

Benoît Paul Émile Clapeyron and his universal law

Finally in the 1830s, Mr Clapeyron combined the above laws into a universal gas law, one law to rule them all.

Where R is the universal gas constant, which is about 8.31 and you absolutely don't need to know why.

I really want to know why

Oh okay then.

It's actually 8.31446261815 to start with but you'll be forgiven for not remembering beyond two decimal places in the heat of the exam.

R is the energy per mole per kelvin required to raise the temperature of an ideal gas.

R comes from combining:

- The Boltzmann constant (energy per particle per kelvin)

- Avogadro’s number (particles per mole)

If you multiply these two together:

- 1.380649 × 10-23 m2 kg s-2 K-1 x 6.02214076 × 1023 mol-1

You get 8.31446261815 J⋅K⁻¹⋅mol⁻¹

What does 'ideal' mean?

The ideal gas laws assume:

- The particles have no volume

- There are no forces between the molecules

- All collisions are perfectly elastic with no loss of energy

So, yeah, not exactly perfect models of the real world, but actually a lot of gases seem to behave remarkably predictably when modelled with these equations.

Syllabus

- PC_BK_19 Physics of gases. Gas Laws: kinetic theory of gases, Boyles, Henry’s, Dalton, Charles, Gay-Lussac

In summary

Universal gas law

- PV = nRT

Boyle's Law

- V1P1 = V2P2 at a given temperature

You use this law to calculate how much oxygen is in your cylinder.

Charles' law

- V is proportional to T for a given pressure

Gay-Lussac's law

- P is proportional to T for any given volume

This is why you don't want sealed cylinders to get too hot.

Dalton's law

- Total pressure = sum of all the partial pressures

Too much nitrous oxide will make your gas mixture hypoxic.

What is standard temperature and pressure?

- 273.15 K

- 100 kPa

The calculations won't work if you use °C.

Five example exam questions

Just to show what we mean.

Question 1

You are performing a gas induction on an anxious three year old child, when the student ODP asks why you've put the sevoflurane all the way up to 8%.

Which of the following is true regarding Fick's law of diffusion?

- The rate of diffusion across a membrane is exponentially proportional to its cross-sectional area

- The rate of diffusion across a membrane is directly proportional to the concentration gradient across it

- The rate of diffusion across a membrane is directly proportional to the thickness

- Fick's first law describes how molecular diffusion causes the concentration to change over time

- Fick's second law describes the movement of molecules down a concentration gradient

Answer

- The rate of diffusion across a membrane is directly proportional to the concentration gradient across it

Adolf Fick proposed two laws in 1855, both related to the diffusion of molecules down a concentration gradient.

In short:

- Rate of diffusion is directly proportional to the area of the membrane

- It is also directly proportional to the concentration gradient

- It is inversely proportional to the membrane thickness

His first law talks about the movement of molecules down a concentration gradient, while the second law describes how this movement then causes the concentration gradient to change over time.

An example:

- The lung has an enormous surface area, which speeds up gas exchange

- Anything that reduces the surface area (lobectomy, collapse, emphysema) will thus reduce efficiency of gas exchange

- Infection and oedema will thicken the effective alveolar-capillary membrane, therefore reducing the rate of gas exchange further

- This can be countered clinically by simply increasing the concentration gradient (FiO2)

- It's also the reason you whack the sevo up to 8% for a faster gas induction

Question 2

Your consultant has reluctantly agreed to do some Monday morning viva practice on the ideal gas law.

Which of the following is not an assumption implicit in the ideal gas law?

- A gas is formed from a very large number of particles of negligible size

- There are no intermolecular forces

- All and any collisions occurring between particles are assumed to be perfectly elastic in nature

- The average kinetic energy is proportional to the absolute temperature

- All molecules are assumed to have similar kinetic energy levels

Answer

- All molecules are assumed to have similar kinetic energy levels

It is accepted that there will be a variety of energy levels between the gas molecules, however the average kinetic energy will be proportional to absolute temperature.

All of the other assumptions are correct.

The ideal gas law combines Boyle's, Charles' and Gay-Lussac's laws into one:

- PV = nRT

Where:

- P = pressure in Pa

- V = volume in metres cubed

- N = number of moles

- R = 8.314 (universal gas constant)

- T = temperature in Kelvin

Question 3

You're looking at a worryingly low PaO2 on a blood gas result and questioning your arterial line skills, when you decide now is a good time to revise Dalton's law of partial pressures.

Which of the following is false regarding Dalton's law?

- Dalton's law states that the total pressure of a gas mixture in a container is the sum of the partial pressures of the individual component gases within said mixture

- Dalton's law assumes that each gas behaves independently of the others

- The pressure exerted by each gas is inversely proportional to the number of moles, assuming temperature and volume remain constant

- The total pressure of the gas mixture is independent of atmospheric pressure

- Removal of one component gas from the mixture will have no effect on the partial pressures of the other component gases

Answer

- The pressure exerted by each gas is inversely proportional to the number of moles, assuming temperature and volume remain constant

The pressure will be directly proportional to the number of moles of gas present, as per the ideal gas law PV=nRT.

All of the others are true.

Question 4

You are driving to work on a brisk winter day when your FRCA-addled brain starts thinking about the pressure in your car's tyres. You realise that you measured the tyre pressure when the tyres were cold, but as they warm up while driving, the pressure must increase at least a little.

Which of the following laws describes this phenomenon?

- Charles' law

- Gay-Lussac's law

- Boyle's Law

- Henry's Law

- Dalton's law

Answer

- Gay-Lussac's law

We're talking about a fixed volume of gas, and noting that the pressure increases in proportion to an increase in temperature, which is Gay-Lussac's third perfect gas law.

- Charles' law = for a fixed mass of gas at constant pressure, volume is proportional to temperature

- Boyle's law = for a fixed mass of gas at constant temperature, the volume is inversely proportional to the pressure

- Henry's law = the partial pressure of dissolved gas in a liquid is in equilibrium with partial pressure in the gas mixture above the liquid

- Dalton's law = the total pressure of a gas mixture is the sum of the component partial pressures

Question 5

Your overly-eager FRCA study buddy has presented you with a deck of flashcards labelled with eponymous terms including Dalton, Henry, Fick and Graham, and has instructed you to 'pick a card, any card'.

Which of the following accurately describes Graham's law?

- The rate of diffusion of a gas is directly proportional to the square root of its molecular weight

- The rate of diffusion of a gas is inversely proportional to the square root of its molecular weight

- The rate of diffusion of a gas is exponentially proportional to the square root of its molecular weight

- The rate of diffusion of a gas is directly proportional to the cube root of its molecular weight

- The rate of diffusion of a gas is inversely proportional to the cube root of its molecular weight

Answer

- The rate of diffusion of a gas is inversely proportional to the square root of its molecular weight

Smaller molecules diffuse faster.

- A molecule four times larger will diffuse at half the speed.

- It partially explains the second gas effect seen with Nitrous Oxide, whose molecules are substantially smaller than those of the volatile agents.

Here's our video

Related posts

Primary FRCA Toolkit

Members receive six months of free membership in return for a purchase of the FRCA Primary Toolkit, which can be redeemed at any time.

Please don't hesitate to email Anaestheasier@gmail.com if you have any questions!