Pharmacokinetics in major haemorrhage

Pharmacokinetics is a tricky enough topic to get your head around all by itself, but things get even more interesting when you add major haemorrhage into the mix.

Let's start with the four pillars of pharmacokinetics:

- Absorption

- Distribution

- Metabolism

- Elimination

Just give me the TLDR summary

- During the bleeding phase, your drugs will seem more potent, act unpredictably and last longer

- During the resuscitation phase, they will do the opposite

You'll see an early overdose, a late underdose, and then a hangover.

What's actually happening?

Blood is being lost from the body at a rate substantial enough to cause the patient (or nurses/med reg/bus driver) concern.

Therefore any drug contained within that blood is also lost.

One can imagine a laughably theoretical situation where the entire circulating volume is lost in one arm-brain circulation, meaning the whole dose of administered drug ends up on the floor.

- This would be the only time that an intravenously administered drug could have a bioavailability of 0%

However this is by definition entirely academic and does little to inform our management of the average bleeding patient.

Most patients with significant bleeding will be somewhere along the spectrum from 'all the drug is in the intravascular space' to 'none of the drug is in the body any more', and it's useful to know how you have to adapt your technique depending on where upon this spectrum they lie.

Let's break it down into two phases:

- The bleeding phase

- The resuscitation phase

Each phase causes its own dramatic pharmacokinetic shifts that need to be considered.

The bleeding phase

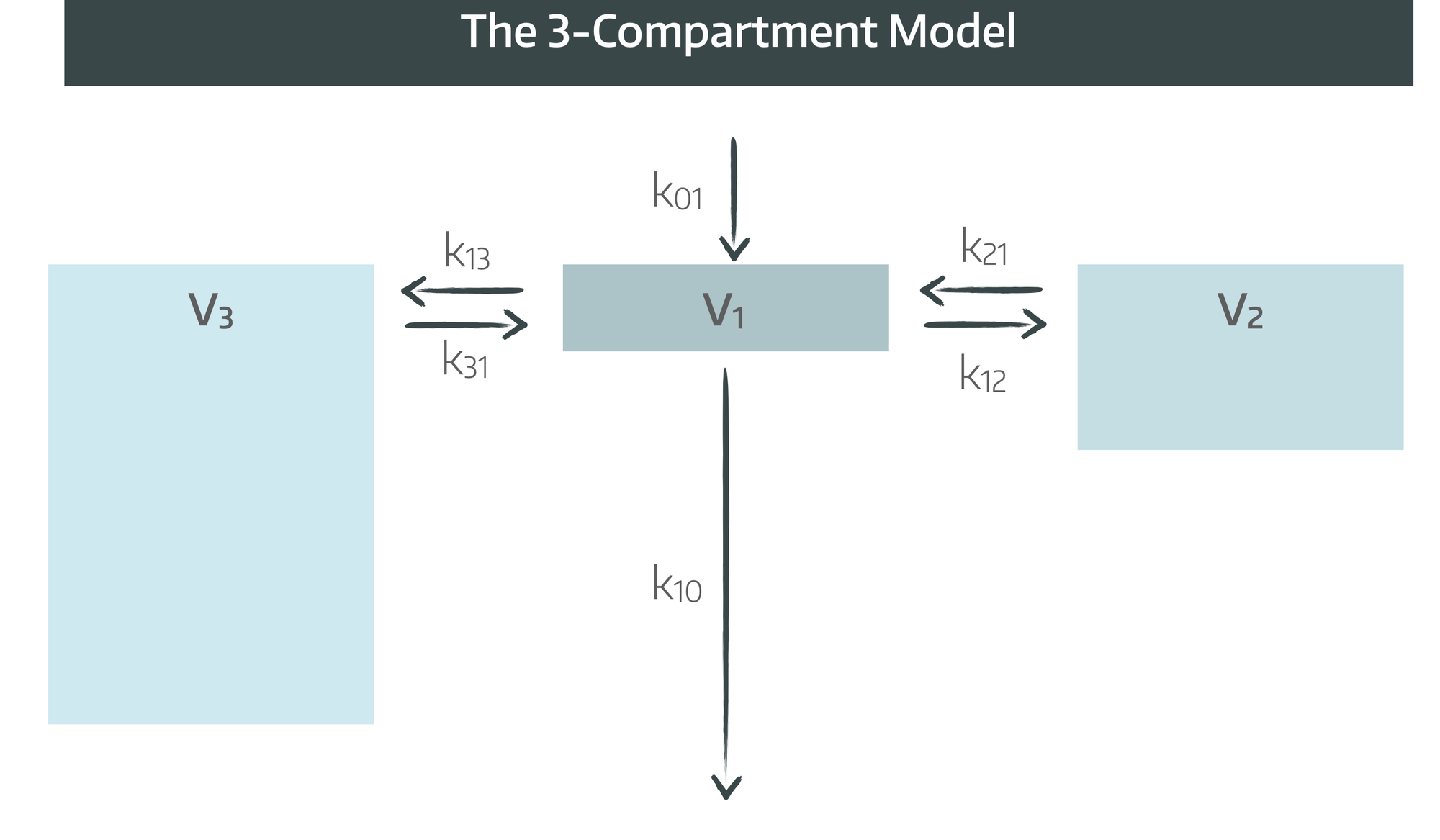

Blood is being lost from the central compartment, meaning the initial volume of distribution drops significantly.

- This increases the initial peak plasma concentrations of any drugs you shove through the cannula

- Reduced organ perfusion means reduced delivery to effect site and unpredictable onset time

- It also means reduced distribution into fat

- You're also dealing with a progressively more acidotic patient, which is going to dramatically alter protein binding

- They're likely to be increasingly hypothermic too

- Now add in an enormous surge of endogenous catecholamines

It becomes clear that our drugs are unlikely to behave as we would usually expect them to.

Then you start rapidly infusing fluids and blood products.

The resuscitation phase

The game has changed. Now we're flooding large quantities of fluid (of varying components and tonicity) into the central compartment, and some of it might be falling straight back out again.

- Plasma concentrations drop as volume is restored

- Protein binding changes depending on what you're infusing

- You may need to increase infusion rates to a new equilibrium

- The patient is warming up

- The acidosis is being corrected

- Calcium is being administered

It all gets rather interesting.

Absorption

We could go into the nuance of how hypoperfusion of the GI tract would impact enteric absorption of orally administered drugs, but we're anaesthetists, so let's jump straight to assuming we're giving everything IV, IO or via some sort of CVC.

- Bioavailability of IV administered drugs can reasonably be assumed to be 100%

- Major haemorrhage will make IV access more difficult

- Delivery to the effect site is flow-dependent

But that's about as far as it goes with the first pillar of pharmacokinetics, so we can move onto distribution.

Distribution

This is where the biggest changes occur.

- The sudden drop in circulating volume means the initial volume of distribution of intravenous drugs decreases

- This means the peak plasma concentration rises

Then it depends on whether the patient is still perfusing their organs and fatty tissues.

- If they aren't perfusing fat very well, the volume of distribution of lipophilic drugs will drop

- If they aren't perfusing other organs very well, then the volume of distribution of hydrophilic drugs will also drop

- If you've got them on noradrenaline and they're extremely peripherally shut down but perfusing their head well, you'll get a rapid onset of action of induction agents

- If they're hypoperfusing their brain, the onset of sedation will be delayed (and harder to determine as they're likely to be rather unconscious already)

When you then plough a litre of balanced isotonic crystalloid because you have no blood available, the volume of distribution increases for both, but disproportionately so for the water soluble drugs - including antibiotics.

If you have a patient who has lost a lot of blood, is now increasingly acidotic in the throes of an enormous systemic inflammatory response, and you've just flooded in three litres of fluid, then:

- Their protein binding is going to drop dramatically

- The free fraction of highly protein bound drugs will increase

- But there will also be a diluting effect of the newly acquired volume

- This may or may not be delivered to the target tissues depending on their perfusion and the degree of microcirculatory failure

- Drug that was previously distributed into fatty tissue can become 'trapped' during periods of hypoperfusion, only to seep back into the circulation later on and cause unexpected mischief

Metabolism

The effect of major haemorrhage on a drug's metabolism is going to depend on the drug itself, how it is usually metabolised, and how bad the haemorrhage is.

- If the drug relies on hepatic uptake and biliary excretion (rocuronium) and you aren't perfusing the liver, then the drug will last longer

- If the drug is metabolised by plasma esterases (suxamethonium) and you've replaced the plasma with esterase-free crystalloid, then the drug may last longer, particularly in the presence of hypothermia, acidosis, or pre-existing cholinesterase deficiency (like pregnancy)

- If the drug spontaneously explodes (atracurium) then it's not going to be hugely affected by changes in its environment, unless the rate of reaction changes with temperature or pH

- If you're not perfusing anything, then none of this really matters anyway

Drugs with high hepatic extraction ratios (like propofol) are dependent on hepatic blood flow for their clearance.

- In major haemorrhage there is decreased hepatic perfusion

- Plasma concentrations will rise for a given infusion rate

- There will be longer duration of action

- Small boluses can have an exaggerated effect

If you then resuscitate them effectively and restore hepatic flow, the plasma concentration can then drop rapidly.

Elimination

Drugs can be excreted by many routes and as a general principle major haemorrhage means lower perfusion of said route, and therefore reduced elimination.

The main organs of concern:

- Liver

- Kidneys

- Lungs (volatiles)

Many drugs produce active metabolites that are renally excreted (e.g. morphine-6-glucuronide).

During major haemorrhage, the parent drug (e.g. morphine) may appear to wear off, while metabolites quietly accumulate and can then cause delayed sedation or respiratory depression.

Does it matter what I give them?

Absolutely, the pharmacokinetics is going to be affected by which fluid you're choosing to resuscitate your poor patient with.

Fluids

- Crystalloid will expand the volume of distribution for hydrophilic drugs like antibiotics

- It will also dilute albumin and clotting factors, increasing the free fraction of those highly protein bound drugs

- Increased tissue oedema will make distribution into tissues unpredictable

- Crystalloid-induced acidosis and hypothermia will exaggerate the previously mentioned effects of these two parameters

Blood products

- Red cells will improve oxygen delivery and organ function

- Plasma proteins in FFP will increase binding, and reduce free fraction of highly bound drugs

- Citrate will cause hypocalcaemia, worsen hypotension and thus perfusion

- If not warmed, these infusions will make hypothermia worse

- If, meanwhile, you were to resuscitate your patient exclusively with 20% human albumin solution, the free fraction of drug would plummet as it all gets mopped up by the mercenary albumin molecules.

This would most likely however be the least of your issues.

So what should I do?

Your best.

Maintain oxygen delivery to the brain and vital organs, do your best to maintain cardiorespiratory homeostasis, employ judicious use of fluids to maintain perfusion without causing overload, keep them adequately unconscious and pain free.... the usual.

The fact that the patient is actively haemorrhaging and their pharmacokinetics might be a little different doesn't change your overall management approach, it just means you need to keep a few things in mind.

Some key things to consider:

- Propofol and other induction agents will have an exaggerated cardio-depressant effect as a bolus dose

- The patient may need a bigger infusion dose as you restore their circulating volume

- TCI models are not validated in major haemorrhage

- Hypotension and cerebral hypoperfusion will drop your BIS (this is bad)

- Neuromuscular blockade may last substantially longer than expected

Some interesting research

- These guys found that steady state propofol infusions produce massively increased plasma concentration during major haemorrhage in pigs

- These guys found that levels of remimazolam aren't affected to the same degree (as one would expect), again in some unfortunate pigs

- These guys agree that propofol is a poor choice of induction agent in an acutely unstable haemorrhaging patient

Does the type of bleeding matter?

Yes, if you want to get a bit more nuanced.

- Slow insidious pelvic oozing will have much less pharmacokinetic impact than a torrential aortic haemorrhage

- Thoracic bleeding with tamponade will have an exaggerated impact on cardiac output and therefore organ hypoperfusion and drug delivery

- GI bleeding often occurs in comorbid, vasoplegic patients with deranged liver function as a baseline

- Obstetric haemorrhage starts from a higher plasma volume as a baseline with increased clotting factor activity

What am I supposed to do with this information?

Simple:

- Resuscitate your patients as you would normally

- If you can wait until the bleeding has stopped to give a drug like an antibiotic where the concentration and dose really matters, then do that

- If you're giving an induction agent, you almost certainly need to use less as a bolus dose

- If you're running TIVA, the required dose is likely to rise as you resuscitate them and restore their circulating volume and organ perfusion

- Respond to changes in physiology quickly and carefully

And most importantly:

Read this post to feel better:

Related posts