Status Epilepticus and Epilepsy

Take home messages

- Seizures look scary but generally don't do significant harm by themselves

- A perioperative seizure can prevent a person from driving for a year

- Well controlled epilepsy carries a normal life expectancy - poor seizure control does not

A spot of history

Seizures are scary to witness even when you understand what's going on, so one can only imagine how terrifying they must have been to ancient civilisations whose only reasonable explanation for what they were seeing was demonic posession.

"His neck turning left, hands and feet are tense, and his eyes wide open, and from his mouth froth is flowing without him having any consciousness"

This Eminem-first-draft-sounding account actually comes from an Akkadian tablet discovered in Mesopotamia, dating back around 4000 years, and it is deemed to be the first documented account of epilepsy.

For millenia it was assumed that not only was this disease some form of divine intervention, but it was assumed to be contagious and as a result patients with epilepsy suffered horrible discrimination right up until the 20th century.

The Egyptians figured out it probably had something to do with the brain, with the rather disturbing documentation of a man with "a gaping wound in his head" who would "shudder exceedingly" when they prodded it.

It was only much later when Hippocrates came along far that it was deemed to be an organic, and crucially non-contagious disease of the central nervous system.

What is a seizure?

It's usually fairly easy to spot a seizure when you see one, but what exactly is going on?

It's an episode of abnormal synchronised electrical activity in the brain, resulting in some form of motor, sensory or autonomic dysfunction.

Seizures can either be partial or generalised. Partial seizures only affect one side of the brain and can in turn be simple or complex, depending on whether consciousness is impaired.

Generalised seizures generally feature symmetrical bilateral (both hemispheres) electrical activity with impaired consciousness with or without muscle contractions.

What are the types of seizure?

- Partial (focal) or generalised, or mixed

Partial

- Simple - maintained consciousness

- Complex - impaired consciousness

Generalised

- Absence

- Tonic-clonic

- Tonic

- Clonic

- Atonic

- Myoclonic

A single seizure does not an epileptic make.

Seizures can be primary (unprovoked, as in epilepsy) or secondary (such as a febrile seizure due to infection).

Epilepsy is a condition wherein the person is prone to unprovoked seizures, which may or may not have an identifiable underlying pathology to explain it.

How is epilepsy diagnosed?

- Two unprovoked seizures at least 24 hours apart

- History combined with EEG abnormalities

Only around 45% of people who have an unprovoked seizure will develop epilepsy.

As many as 4% of patients without epilepsy will show some form of seizure-esque activity on an EEG, and up to 50% of patients with epilpesy will have plumb-normal EEG scans.

Hence a good history and preferably witnessed episode is vital for a secure diagnosis.

It's rather common

There are over half a million people living with epilepsy in the UK, so chances are one of them is going to wander into your anaesthetic room at some point.

It's also twice as common in children as adults.

This means you need to be aware of what it is, how to manage it, and crucially - how to avoid making things worse during the perioperative period.

Why does epilepsy happen?

This undesirable excessive electrical activity in the brain is thought to happen as a result of three processes:

- Loss of post-synaptic inhibition and reduced GABA activity

- Increased excitatory glutaminergic synapses

- Presence of pacemaker neurones with defective voltage-gated calcium channels

We think. To be fair, this all sounds reasonably logical, as any loss of inhibition, increase in stimulus and a mis-firing pacemaker cells is quite likely to result in unwanted electrical activity.

What are the causes of epilepsy?

Around 60% or so is idiopathic, with no underlying cause identified.

Other causes include:

- Congenital syndrome

- Trauma

- Neoplasia

- Infection

- Metabolic disorders

- Multiple sclerosis

- Neurodegenerative disease

- Cerebrovascular disease

How is it treated?

Most patients with epilepsy find adequate control with a titrated regime of antiepileptic medication, which gives them relief from seizures and allows them to continue a relatively normal life.

In some cases, however, this isn't sufficient, and some patients go on to require varying forms of surgery to physically remove the offending neurons.

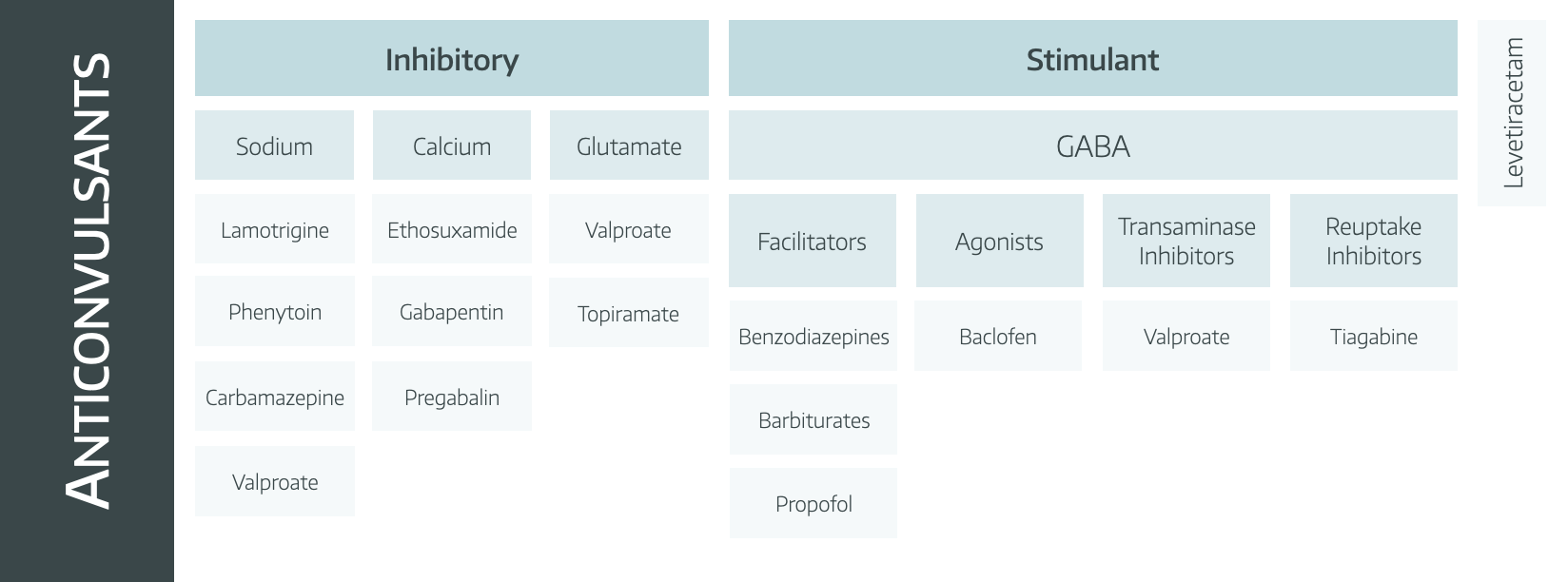

How do anticonvulsants work?

We won't go into the full ins and outs here on the pharmacology of anticonvulsants here, as that will be covered in a dedicated anticonvulsants page, but we'll do a quick recap.

Essentially you want to either:

- Suppress excitatory neuronal activity, or

- Increase inhibitory activity

To do this, you unsuprisingly want to target some sort of ion channel, and those targets are listed in the image below.

Clearly it would be nice just to use one of these agents and be done, and that's what we aim to do, starting with monotherapy and increasing the dose, but if needs be, more agents can be added in.

Click here for a table with everything you could possibly want to know about all the anti-epileptic drugs.

How does Keppra work?

Great question - magic.

- We know it binds synaptic vesicle protein (SV2)

- It also inhibits pre-synaptic calcium channels

- Unclear exactly how it works, but it does, and we like it

Can patients be cured?

- If you are diagnosed with epilepsy, and then proceed to go ten years without a seizure, having taken no antiepileptic medications for that time, then you are no longer considered to be epileptic

- Alternatively if it's a paediatric or age-dependent seizure syndrome that they have grown out of, they can be considered not to be epileptic

- Surgical resection can be definitively curative in some circumstances

We will discuss anaesthesia for epilepsy surgery in a separate dedicated post, once we get around to writing it.

What is status epilepticus?

A seizure that is still happening.

Technically it is defined as a seizure lasting 30 minutes but everyone seems to have unianimously agreed that seems like an unreasonably long time to wait before doing anything to help.

- It's a big deal, with a 25% mortality (This is negatively skewed - less than 10% in kids and up to 50% in elderly)

- In around 33% of cases it is a first presentation of epilepsy

How to manage status epilepticus

You've arrived in the emergency department to a panicking crowd surrounding a shaking, writhing patient who may or may not have IV access or an airway - where to start?

Easy answer is ABCDE as always, but it's good to think about what you're trying to achieve in this scenario.

Your immediate aims

- Terminate the seizure

- Reduce cerebral oxygen demand

- Treat underlying cause of the seizure

- Anticipate, prevent and treat any complications

To achieve these things you can break the clinical scenario up into blocks of time as follows:

First five minutes

- Airway - recovery position, jaw thrust, adjuncts

- Breathing - high flow oxygen is a good idea given raised oxygen demand

- Circulation - IV or IO access, send off bloods and blood gas analysis

- Disability - check glucose

- Exposure - apply monitoring and look for evidence of injury

Most seizures self-terminate, but if you've done the above and they're still seizing, move on to the next block.

The next ten minutes

If the patient has been seizing for five minutes, then they're in status eplipeticus, and require pharmacological intervention.

If IV access

- Lorazepam 4mg IV or

- Diazepam 10mg IV

If no IV access

- Midazolam 10mg buccal or

- Diazepam 10mg PR

If still seizing after 5 more minutes, give another dose, and make sure you have IV access ASAP.

The next ten minutes

This is now established status epilepticus.

Time to employ one or more of the following:

- IV levetiracetam 60mg/kg up to 4.5g max dose over 10 mins

- IV phenytoin 20mg/kg up to 2g max dose

- IV valproate 40mg/kg up to 3g max dose*

*Ideally avoid in women of childbearing age

At this point ICU should probably know about the patient.

After 30 minutes

This is now refractory status epilepticus.

The assumption is you have given at least 2 doses of benzos, and at least one dose of an antieplipetic from the previous box.

Now it's time for general anaesthesia, and propofol, thiopentone, ketamine and midazolam are all reasonable choices.

The key is to ensure adequate maintenance of anaesthesia as well as loading them with antieplipetics for when you try and wake them up.

I'd be amazed if you reach this point, but if your patient is somehow still seizing then you're into the realms of super-refractory status epilepticus.

Super-refractory status epilepticus

We're talking about continued convulsions 24 hours after a successful general anaesthetic.

You definitely need neurology input, and you can consider the weird and wonderful options including:

- Magnesium

- Phenobarbital

- Topiramate

- Vapours such as isoflurane

- High dose steroids

- IVIG

- Plasma exchange

- Hypothermia

- Ketogenic diet on ICU

- Pyridoxine

Don't be doing any of these by yourself please.

Once they've stopped seizing

A patient post-status is likely to be substantially post-ictal, so a low GCS is common.

As with any emergency, you need to go back to the beginning and reasses:

- ABCDE

- A neurological examination is probably sensible once it's feasible to do so

- Start considering why the patient has seized and what investigations need to happen next

- Close monitoring +/- HDU depending on their clinical status

- A chat with neurology about what they'd like to do next is usually a good plan too

What about the 'non' seizures?

This is a tricky topic, but ironically as an anaesthetic registrar I've been asked to come and help with a lot more of these than I have genuine status epilepticus.

We've all seen them in varying presentations, some very convincing and others not so much.

They're tricky to manage, because you can't deny a patient treatment for a seizure because you 'think' it's not a genuine neuronal electrical storm, but equally repeated doses of benzodiazepines for someone who isn't seizing isn't going to do anyone any favours at all.

So what to do?

Always assume it's a seizure to start with, and treat as you would - with 2-4mg of lorazepam or another benzodiazepine.

However if there is increasing suspicion amongst the team that this presentation might be 'psychosomatic' in aetiology and you don't want to risk the patient's airway and respiratory drive with further unnecessary benzodiazepines, then you might consider a little diagnostic saline.

It is very important that you don't lie to your patient, and so I have found success in treating an 'anelectric seizure' by stating confidently:

"The seizure should stop around forty seconds after I give this..."

Before plunging a flush of 0.9% saline firmly so the patient can feel it entering the vein - sure enough, the patient relaxed completely, exactly forty-one seconds later.

This particular patient had already had repeated doses of lorazepam and Keppra to no effect, and this test allowed us to reassure ourselves that we probably didn't need to give any more.

The immediate post-saline return to full Instagram functionality was supportive of our diagnosis.

Anaesthetic concerns

Often you'll be anaesthetising a patient for something completely unrelated to their epilepsy, but you need to think carefully about how you're going to manage them in the perioperative period.

The aim of the game here is to do the following:

- Minimise disruption of routine anti-epileptic regime

- Avoid drugs that cause interactions with anti-epileptics

- Avoid drugs that lower the seizure threshold where possible

- Avoid seizure triggers where possible

Can I use propofol?

Yes. All the induction agents apart from etomidate are absolutely fine at normal anaesthetic doses.

Just be sure to give enough, because at lower doses some of them are pro-convulsant.

Can I use muscle relaxants?

Yes, suxamethonium and rocuronium are both fine except:

- Avoid sux after prolonged status, as it can lead to hyperkalaemia

- Some antiepileptics are enzyme inducers, meaning the patient will chew through enormous doses of rocuronium

- Apparently laudanosine - (our primary FRCA exam superstar metabolite of atracurium) - is proconvulsant, but this hasn't been convincingly demonstrated in humans

Which antiemetics should be avoided in patients with epilepsy?

It's probably best to avoid any drugs that might have side effects that can be confused with seizure activity, such as dystonias and extrapyramidal effects, as they will just muddy the waters for your management.

- Prochlorperazine

- Metoclopramide

- Droperidol

Which drugs do enzyme inducers affect in the post-operative period?

- Antibiotics

- Paracetamol

- Fentanyl

In return, some drugs can increase the concentration of antiepileptic medications by inhibiting their metabolism, so it all gets rather complicated.

Just Google it on the day.

I did not tell you to do that.

You might often see a patient shaking rather sportingly after a general anaesthetic, particularly if you've used sevoflurane or another volatile agent. These are usually not seizure activity, and genuine drug-induced seizures are relatively uncommon.

Of course - seizures are much more common after neurosurgery, as the brain doesn't enjoy being poked about.

Primary FRCA Syllabus

- PR_BK_30 Benzodiazepines: classification of action. Clinical actions. Synergism with anaesthetic agents. Antidote in overdose

- PR_BK_58 CNS: antiepileptic agents: Mechanisms of action; unwanted side effects

A free CRQ from FRCA-revision.com

Useful Tweets and Resources

Click the image for a brilliant management flow chart from Leeds teaching hospitals.

Epileptogenic potential, seizure threshold and altered hepatic metabolism; Epilepsy in a pregnant woman and anaesthesia,#BJAEducation #anaesthesia #OBanes #MBBRACE@YavorRM https://t.co/qxlE6XwsKR pic.twitter.com/121KzCAuHs

— British Journal of Anaesthesia (@BJAJournals) June 11, 2021

References and Further Reading

Primary FRCA Toolkit

While this subject is largely the remit of the Final FRCA examination, up to 20% of the exam can cover Primary material, so don't get caught out!

Members receive 60% discount off the FRCA Primary Toolkit. If you have previously purchased a toolkit at full price, please email anaestheasier@gmail.com for a retrospective discount.

Discount is applied as 6 months free membership - please don't hesitate to email Anaestheasier@gmail.com if you have any questions!

Just a quick reminder that all information posted on Anaestheasier.com is for educational purposes only, and it does not constitute medical or clinical advice.