Inhaled Foreign Body

Take home messages

- Young kids put everything in their mouths

- Bradycardia is due to hypoxia until proven otherwise

- Local anaesthetic is your best friend

Paediatric emergency to resus

"Please don't be choking, please don't be choking..."

If you were to list the most terrifying paediatric emergency cases to come crashing into your local resus bay, airway compromise due to an inhaled foreign body has to be up there in the top... three?

Inhaled foreign body can of course affect anyone with an airway - and access to things smaller than said airway - but it tends to crop up more frequently in children, so we'll focus on the paediatric side of things for now.

Here's what you need to know.

How bad is it?

Upon whipping back the curtain you're going to rapidly establish just how bad the situation is, which is anywhere on the spectrum from:

- totally fine and unsure why they're here

- maybe a spot of whistling or stridor

- possibly a tad short of breath

to:

- peri- or -intra-arrest

- blue

- drooling, tripodding and very sick indeed

And from there you can figure out your next steps.

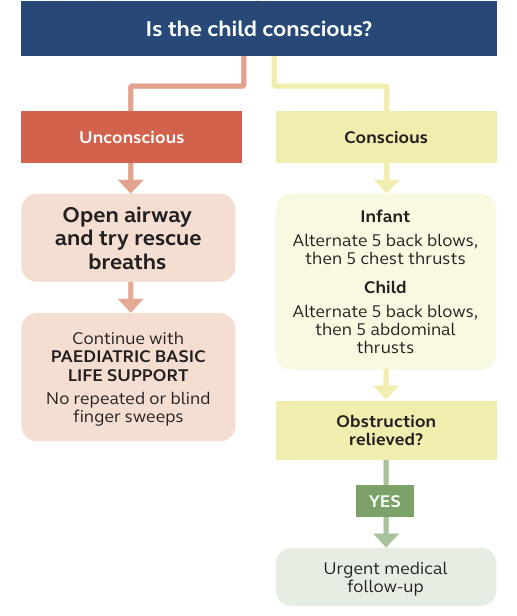

If you're presented with a patient in arrest or very close to it, then you're heading down the BLS/ALS/APLS choking and hypoxia algorithms. Hopefully someone has already done some back slaps and chest thrusts but it never hurts to check - we often forget the basics in a stressful situation.

A quick reminder of said basics

AMPLE history

- Allergies

- Medications

- Previous medical and anaesthetic history

- Last meal

- Events prior to now

The not-quite-so-sicks

For now we'll focus on those patients that have aspirated but are relatively stable, and what you need to do about it.

The issues that need resolving:

- We need to assess what has been aspirated and where it is

- We need to assess the child's respiratory status, and determine how much support they need, if any

- We need a plan to get the foreign body out

- This usually requires an anaesthetic of some sort

What are the signs that a child needs immediate surgical intervention?

- Drooling

- Hoarseness

- Difficulty swallowing

- Significant stridor

- Tripodding

- Cyanosis

- Hypoxia

- Drowsiness

- History of dangerous object inhaled (think batteries, magnets or something sharp)

You're allowed to cough and splutter when you aspirate, but you should settle down afterwards. Ongoing distress is a sign that you need something doing about it.

What issues do you need to think about?

- Distressed child

- Distressed parent

- Hypoxia

- Avoiding making everything worse

- A highly stimulating airway intervention with an already compromised airway

- Unfamiliarity with the procedure (if in a DGH that doesn't do paediatric ENT emergencies all that often)

- Sharing the airway with a surgeon

Investigations

This is going to depend heavily on what state the child is in.

An awake, comfortable, mildly stridulous infant with no respiratory distress or significant airway compromise usually has time for an xray to try and locate a radio-opaque object such as a coin, button battery or magnet.

A peri-arrest choking child in whom APLS manoeuvres have not worked does not.

Other Xray signs to look for include:

- Pneumothorax

- Collapse

- Pneumonia

- Hyperinflation

How do I anaesthetise them?

Call for experienced help.

Even if you end up doing most of it yourself because the child is so unwell and needs stuff doing right away, you definitely want experienced hands on deck as soon as possible.

Children are like a rhino on a skateboard - they go downhill very quickly.

Call your boss, call their boss, call anyone's boss - just don't be alone in 20 minutes time.

Induction of anaesthesia

The first thing to say is you do what you can, with what's in front of you.

Much of the time your hand is forced by the situation, and you have to make do with the equipment, drugs and location available to you, because the child is too sick to move etc. so you might find yourself doing a classical RSI and intubation in resus because it's all you can do.

But If you have the luxury of choice:

The exam answer is often a gas induction using sevoflurane and 100% oxygen as this gets the child asleep without the added stress of cannulation.

You can of course do an IV induction instead, but with smaller doses than usual because ideally you don't want them to stop breathing.

- Fentanyl 0.5 mcg/kg

- Propofol 1 mg/kg

Then top up with aliquots of propofol until they're asleep.

You can consider a premed - something like midazolam or clonidine - a distressed child is a higher risk child, but only if there is no concern about losing the airway as a result.

Ventilation

The theory (and exam question) goes that mechanical ventilation is bad because it might push the foreign object further down and make it harder to retrieve.

This might be true - it might also be a heap of rubbish - but it feels sensible to keep the child spontaneously breathing (devil you know and all that).

Having said that, in a desperately hypoxic child, some PPV might shove an object from obstructing the trachea to only obstructing a single bronchus, thereby saving the child's life, so there's also that.

Maintenance of anaesthesia

Same options as usual - gas or TIVA.

- TIVA has the substantial benefit of being airway independent in case of difficulty at the head end

A sensible regime would be

- Propofol 250 mcg/kg/min

- Remifentanil 0.2 mcg/kg/min

The key here is having the patient as deep as possible while still breathing - you don't want a child coughing and moving with a rigid bronchosope in their trachea.

Local anaesthetic

Airway manipulation is notoriously stimulating, especially in a child that is spontaneously breathing.

Rather than just getting them deeper and losing their respiratory drive, make your life (and that of the surgeon) easier by applying lots of topical local anaesthetic (up to 4mg/kg lidocaine) to the asleep airway as well.

Spraying concentrated lidocaine liberally throughout the oropharynx, glottis and subglottis will hugely reduce the required amount of sedation for the procedure.

It's also a good test of readiness for the procedure - if the lidocaine spray is making them cough, they're not ready for the operation.

How to oxygenate them

Understandably, a small airway that is currently largely occluded by a foreign body - that has then had a rigid bronchoscope thrust into it - is often rather a challenge to ventilate, and oxygenate.

Oxygenation and ventilation in this instance require careful coordination between surgical and anaesthetic teams, and will depend on the child's respiratory effort, degree of obstruction and how quickly they can find it and whip it out.

Depending on the bronchoscope you might have some cool options available to you.

- A ventilating bronchoscope has a 22mm connecter on the side, which will accept a breathing circuit

- If the surgeon is doing things to the larynx then you can stick standard oxygen tubing onto the surgical laryngoscope

- Otherwise you can slip a nasal tube in, down to the nasopharynx and oxygenate just superior to the larynx

- Optiflow is always an option as well

Clearly these is much easier if the patient is spontaneously breathing.

Bear in mind you probably won't have a reliable ETCO2 trace, given the amount of unsealed airway instrumenting going on, so you do end up having to rely on the fact that you're maintaining a decent respiratory effort, suppling enough oxygen, keeping the sats up and the procedure as short as possible.

Afterwards

Hopefully you've managed to keep them breathing, oxgyenated and comfortable, and the surgeon has fished the nasty out of the trachea and you've succeded in waking the patient up without much issue.

Your post operative concerns include:

- Pain

- Airway swelling and oedema

- Bleeding from trauma to airway

- Respiratory distress from lung collapse and derecruitment

- Infection

Sensible things to do

- Paracetamol and ibuprofen

- Nebulised adrenaline

- Dexamethasone 0.25-0.5mg/kg

- Physiotherapy or breathing exercises

- Low threshold for antibiotics, if evidence of infection or prolonged time since aspiration

Useful Tweets

Click on this link if you dare:

https://twitter.com/cleebennett/status/1620457521050943488

The difficult paediatric airway = #SCARY. Upper airway obstruction in children – broad range of presentations, three important diagnoses; Croup, Epiglottitis and Inhaled Foreign Body. Here’s some #OnePagers.#JanuAIRWAY 3/10 pic.twitter.com/ITauhOwvAg

— Difficult Airway Society (DAS) Trainees (@dastrainees) January 24, 2022

“Don’t spill the _____!” In this case, don’t inhale them! Comment with your guess and learn more about Olympus’ line of foreign body retrieval products: https://t.co/HX6eUf9nfo pic.twitter.com/662xomOYX0

— Olympus Medical Americas (@OlympusMedUS) November 21, 2019

References and Further Reading

Primary FRCA Toolkit

While this subject is largely the remit of the Final FRCA examination, up to 20% of the exam can cover Primary material, so don't get caught out!

Members receive 60% discount off the FRCA Primary Toolkit. If you have previously purchased a toolkit at full price, please email anaestheasier@gmail.com for a retrospective discount.

Discount is applied as 6 months free membership - please don't hesitate to email Anaestheasier@gmail.com if you have any questions!