Flap Surgery

Take home messages

- You're likely to encounter flaps in breast and max fax surgery

- Flap failure is catastrophic for patient and surgeon

- Your anaesthetic can heavily influence how well the flap survives

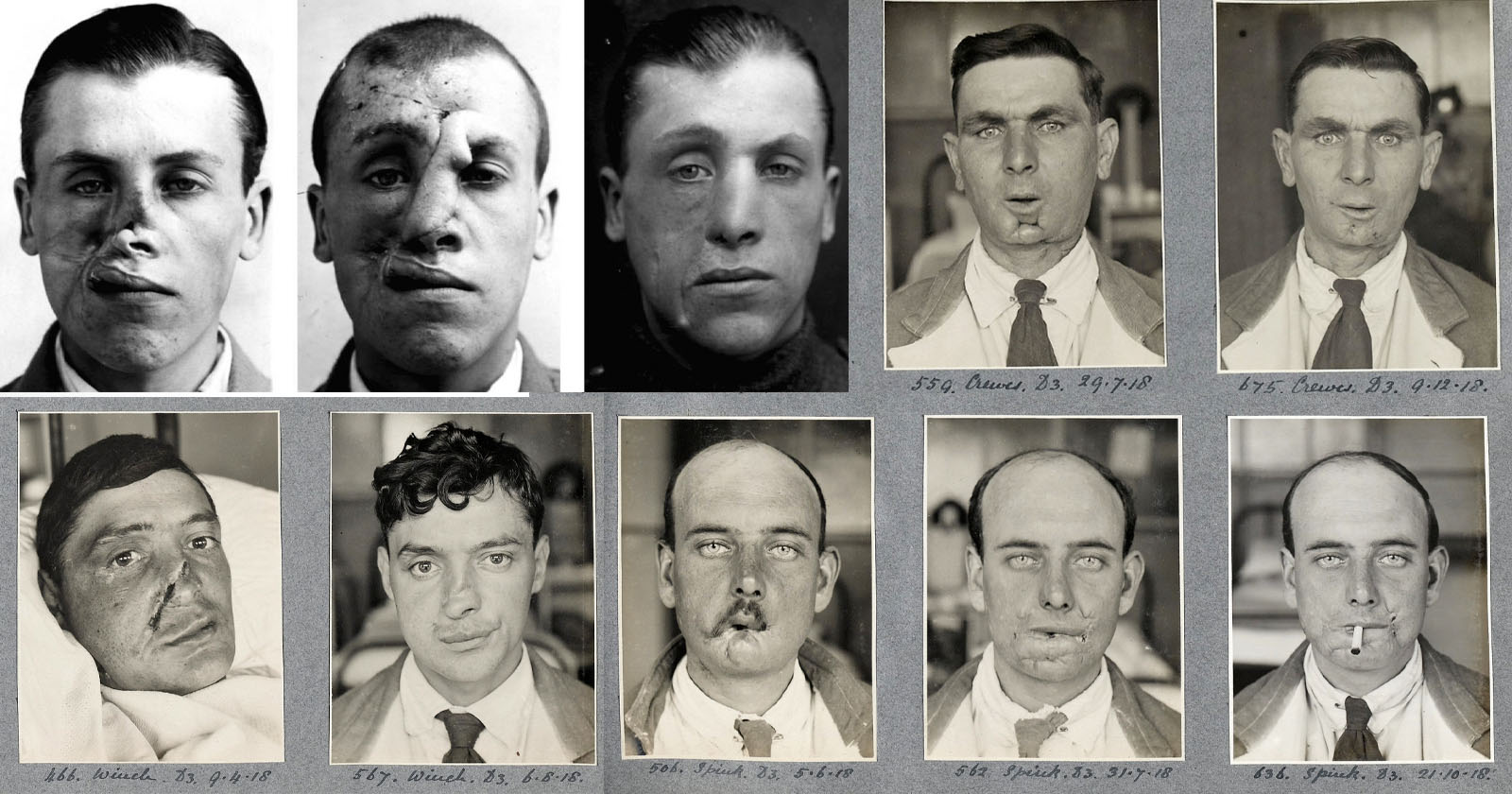

A spot of history

What's really interesting is that pedicled flaps predate any knowledge of the vascular system, antisepsis or anaesthesia.

Apparently, all the way back in around 600 BCE, attempts were made in India at rhinoplasty to restore the facial structure of those unfortunate enough to have had their noses cut off as a form of punishment.

Fifteen different approaches, including pedicled cheek flaps that are still used today are described in the Sushruta Samhita if you're desperate to read more.

Anaesthesia and antisepsis

Prior to the iconic advent of the greatest specialty in the world in 1846, it was understandably tricky to carry out long and complex reconstructive operations, what with the patient moving and screaming and all that.

There was also the issue of a complete lack of understanding of antisepsis until Lister came along in the 1860s, so basically every attempt got horribly infected and failed.

Meet Harold Gillies

This chap is credited with the not-to-be-sniffed-at title of 'father of plastic surgery' as a result of his remarkable efforts at facial reconstruction for soldiers during the first World War.

An ENT surgeon born in New Zealand, Gillies set up the first ever large-scale reconstructive surgery service at the Queen Mary's Hospital in Sidcup, operating on over eleven thousand patients with disfiguring facial injuries.

His signature creation was the tubed pedicle flap, which maintained the blood supply while also protecting the flap from infection as it was transferred in stages to the recipient site.

Gillies’ textbook Plastic Surgery of the Face became foundational reading worldwide.

From the 1970s onwards the success rate of flap surgery and the limits of what was possible exploded with the development of:

- Microvascular surgery

- Operating microscopes

- Finer suture materials

This was when we truly began to see successful free flaps with microvascular arterial and venous anastomoses.

The only slight downside is that the anaesthetic implications became somewhat more complicated too.

Flap time

Rather than describing a surgeon prone to panicking halfway through a procedure, flap surgery refers to the production and then installation of a tissue flap, which can be one of two types:

- Free

- Pedicled

A free flap is as it sounds, you lift a chunk of tissue from somewhere distant to the surgical site of interest (and usually out of sight in day-to-day life) and plumb it into the region you've just operated on.

A pedicled flap remains connected to its original donor site through a vascular pedicle, which maintains the arterial and venous supply.

What's the difference?

As a general rule pedicled flaps involve:

- Shorter surgery

- Less ischaemia and reperfusion injury

- More reliable perfusion

They are however still vulnerable to hypotension and venous congestion.

Three phases

There are many phases to any operation, including faffing, anaesthetic time, more faffing, sign in, faffing and then a bit of cutting.

Then after some more faffing and possibly some faffing about, you can wake the patient up.

Flap surgery is no different, however there are three phases in particular to be aware of.

Lifting the flap

- Flap elevation and vessel clamping

- Meticulous dissection of tissue layers, identifying the key vasculature that will be used for the anastomsis

- Surgeon may want a degree of hypotension to improve field visibility

Ischaemic time

- This is also called 'primary ischaemia'

- It's the period of time where the flap is using anaerobic respiration to survive

- Occurs for up to 90 minutes after clamping

Reperfusion

- The anastomosis is completed and the clamps released

- Hopefully the newly established blood flow washes out the inflammatory mediators and toxins that have built up during the ischaemic time

- A normal blood pressure (i.e. no more than 20% below the patient's baseline) is usually sufficient to ensure adequate perfusion of the new tissue

Why flaps fail

If you think of a free flap as a denervated organ that has minimal ability to autoregulate, then it's a little easier to see why they're so delicate, and why pedicled flaps have a higher survival rate.

- The blood vessels in the flap lose their autonomic supply

- This hampers their ability to autoregulate with changes in blood pressure

- The supplying artery and draining vein of the recipient site, however, will still be able to autoregulate in response to humoral, chemical and neural stimuli

- There's also the fact that loss of lymphatic drainage makes oedema more likely to think about

Choose your patients wisely

I have heard a surgeon calmly state:

"The flap didn't fail, the patient failed."

Many patients having flap surgery (especially those having operations for head and neck cancer) carry numerous other co-morbidities that make life more tricky for everyone involved.

It starts by identifying those at particularly high risk - a free flap is far less likely to succeed in a malnourished diabetic vasculopath who has had radiotherapy to the surgical site.

Risk factors for flap failure

- Smoking - nicotine-induced vasoconstriction, carbon monoxide-induced multifactorial hypoxia and hypercoagulability

- Diabetes

- Peripheral vascular disease

- Anaemia

- Malnutrition

- Previous radiotherapy

- Hypercoagulability (sickle cell, polycythaemia)*

*These are the only true absolute contraindications to free flap surgery.

Flaps need flow

It's impossible to discuss anything involving blood flow without at least nodding to the legendary Hagen-Poiseuille law of laminar flow of an incompressible Newtonian fluid through a stiff cylindrical tube.

Given that blood isn't a Newtonian fluid, blood flow is rarely truly laminar and the vessels aren't stiff cylinders, the only meaningful take-away from this equation that anyone can seem to agree on is that increasing the pressure gradient increases flow a bit, and making the vessel radius larger increases flow a lot.

Therefore to increase blood flow to the flap, you need to:

- avoid unnecessary vasoconstriction (pain, cold, hypotension)

- maintain a decent pressure gradient (fluids, cautious use of vasopressors)

The old chestnut of 'vasopressors kill flaps' is not completely untrue, but also isn't a reason to avoid them - use them carefully to counteract vasodilation and maintain a normal blood pressure.

What are your key priorities as the anaesthetist?

- Maintain perfusion

- Maintain oxygenation

- Facilitate venous drainage

A flap can fail for any one of these three reasons.

Either it isn't receiving enough blood (hypotension, anastomotic failure), or it is hypoxic, or it has become congested (fluid overload, excessive PEEP).

Communication with your surgeon is exceptionally important.

You need to know exactly what stage of the procedure they're on at any given moment, so that you can tailor the haemodynamics appropriately.

Things you can help with

- Hypotension in recovery can cause flap ischaemia and hypoxia

- Pain and hypothermia cause sympathetic vasoconstriction and impair blood flow to the flap

- Nausea and vomiting can cause venous congestion

- Haematoma and bleeding can cause flap compression

What is flap monitoring?

These patients are usually headed to HDU or higher after their lengthy and complex procedure, and intensive care nurses are usually well versed in 'flap obs'.

These are specific parameters that help establish the health of the flap, and whether it remains viable or needs re-fixing.

- Colour

- Temperature

- Capillary refill

- Skin turgor

- Bleeding on pinprick

- Doppler

If it looks like the flap is failing, the likely solution is a return to theatre pronto.

How to anaesthetise them

When presented with any sort of 'how would you anaesthetise a patient for this case' question, break it down into:

- Induction plan

- Maintenance plan

- Emergence plan

These can then be discussed in turn, and you will look like quite the professional.

Induction plan

- The airway plan is usually intubation and ventilation as this is going to be a long procedure

- If this is a head and neck cancer case then you need to think about what kind of tube you need, and how difficult it is going to be to insert

- Large venous access avoiding the operative side where relevant, especially if previous lymph node clearance

- Central access may be required if previous chemotherapy and difficult IV access

- Induction is generally with propofol and opioid, either as bolus injections or as part of a TIVA protocol

Maintenance plan

- TIVA or volatile can be used, however there is an increasing propensity to employ TIVA for its environmental, PONV and cancer recurrence benefits

- Isoflurane helps with blood flow through the microcirculation

- Sevoflurane might improve ischaemia-reperfusion injury

Nothing is definite, and as always, it's more about what anaesthetic is safest in your hands.

Regardless of your anaesthetic technique, the same rules apply:

- It's a long procedure

- Positioning to avoid pressure injury and nerve palsies

- Heat loss

- VTE prophylaxis

- Fluid shifts and balance

- Catheter

Emergence Plan

- Smooth emergence avoiding coughing and straining, as these increase central venous pressure and therefore reduce perfusion pressure to the flap

Options include:

- Deep extubation

- Airway exchange for supraglottic device

- Extubating on remifentanil infusion

Analgesia

The flap, having been sliced mercilessly from whence it came, is insensate, and therefore relatively painless.

The donor site, meanwhile, can be excruciatingly sore.

So, just for a change, we're going to suggest:

- Regular paracetamol and NSAIDs where allowed

- Weak and strong opioids as required

- Adjuncts and additives (lidocaine, ketamine, gabapentinoids, clonidine, magnesium)

- Regional anaesthesia where applicable

What if I think it's failing?

If you (or the ITU nurse) can recognise it early enough - that is within six hours or so - then the salvage rate is pretty decent, around 75%.

- The definitive treatment is re-exploration in theatre to unblock, unkink or re-tie the anastomosis, or remove the compressive haematoma

So your job is getting them there and asleep as quickly and safely as possible.

References and Further Reading

Primary FRCA Toolkit

While this subject is largely the remit of the Final FRCA examination, up to 20% of the exam can cover Primary material, so don't get caught out!

Members receive 60% discount off the FRCA Primary Toolkit. If you have previously purchased a toolkit at full price, please email anaestheasier@gmail.com for a retrospective discount.

Discount is applied as 6 months free membership - please don't hesitate to email Anaestheasier@gmail.com if you have any questions!

Just a quick reminder that all information posted on Anaestheasier.com is for educational purposes only, and it does not constitute medical or clinical advice.

Anaestheasier® is a registered trademark.