Fat Embolism

Take home messages

- The triad of fat embolism syndrome is respiratory distress, neurological disturbance and a petechial rash

- Suspect it in any major trauma or burns patient

- While mortality is 5-15%, mostly it will usually resolve with supportive care

Podcast episode

A Spot of History

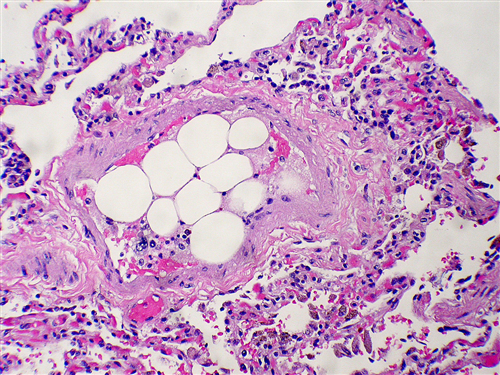

In 1862 an unfortunate railway worker suffered a horrendous crush injury, and at autopsy Dr Zenker noted fat globules in his pulmonary vasculature.

Busy Dr Zenker, who in his spare time discovered trichinosis, also has a diverticulum, a paralysis and a degeneration named after him.

A decade later, Bergmann made the first clinical diagnosis of fat embolism in a patient with a femoral fracture.

Scroll forward a hundred years and in 1970, Gurd develops his infamous criteria, and Schonfeld and Lindeque dip their oars in over the next twenty years, trying to provide better diagnostic criteria for recognising the condition.

We still don't really understand it.

There are two theories

Predictably, large globules of unrestrained fat flowing through one's vasculature is a recipe for disaster, and the exam requires you to be able to explain why, discussing the two theories on the pathophysiology of fat embolism syndrome.

The mechanical theory

- Globules of fat enter ruptured veins at a site of trauma

- These fat globules travel throughout the circulation and occlude the smallest capillaries and arterioles

- This results in a 'pulmonary embolism type' picture of pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular strain

This theory makes logical sense on the surface, but doesn't really account for why many patients only develop symptoms up to 48-72 hours after the traumatic insult.

The biochemical theory

- The fat enters the vasculature as explained above, however rather than a physical occlusive pathology, the harm is caused by a toxic-inflammatory process

- Trauma causes levels of serum lipases to increase, which will in turn upregulate the breakdown of fat into endothelium-busting free fatty acids

- This then leads to endothelial dysfunction, thrombosis and vasospasm

Either way, the lungs end up with pulmonary haemorrhage, oedema, consolidation and atelectasis, resulting in a substantial ventilation-perfusion mismatch and raised A-a gradient.

There is apparently a third theory - the coagulation theory - which is an extension of the mechanical theory. Essentially, instead of the fat globule causing the mechanical obstruction, it triggers a clot to form which does the dirty work instead.

Let's be honest - the answer is probably a bit of all three.

For the exam, just be able to talk about the mechanical and biochemical theories.

What it looks like

But in reality >95% get hypoxia, around 60% get neurological changes and only a third get a rash.

Much like pulmonary embolism, anaphylaxis and bone cement syndrome, FES is a clinical problem that you need to suspect in a patient that you've already recognised as being at high risk, because it can present in a variety of ways, and often many hours after the initial insult.

Suspect fat embolism in any patient with substantial trauma, burns or major orthopaedic surgery.

The clinical features of fat embolism syndrome

The easiest way to present this information is by organ system, but on the understanding that it can vary widely between individuals.

It's often worth mentioning that the patient is usually the recipient of some sort of orthopaedic intervention - be that deliberate or accidental.

Respiratory

- Tachypnoea and dyspnoea

- Hypoxaemia

- Haemoptysis

Cardiovascular

- Tachycardia

- Hypotension

- Right heart strain on ECG

Neurological

- Confusion

- Drowsiness

- Agitation

- Convulsions

Dermatological

- Petechial rash - classically in the folds of the axilla and neck

Haematological

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

Renal

- Acute kidney injury

- Haematuria

- Lipouria

Hepatic

- Jaundice

Other

- Purtscher's retinopathy - cotton wool exudates, haemorrhage and oedema

You might have noticed by now that fat globules in the microvasculature is bad for every organ, so if you're stuck on this question, just start naming a few symptoms from all the organ systems you can think of and you'll probably get all the marks.

Usually the respiratory issues are the first to show - which makes sense given the pulmonary capillary bed is the first stop on the FES train - followed fairly quickly by neurological manifestations, which can be nebulous and variable.

It's possible that intracranial fat emboli can cause inflammation, ischaemia and cerebral oedema, however the main threat to life tends to remain a respiratory issue.

Who gets it?

The vast majority of patients with a femoral shaft fracture have globules of fat in their blood, as do those having intramedullary reaming for long bone operations.

So much like bone cement syndrome in elderly hip fracture patients, and air embolism in resurfacing scuba divers, it's a mixture of how much is embolising, and how capable the body is at handling it, that determines whether you develop the full blown syndrome or not.

It can affect anyone, but there are particular risk factors that predispose to FES, and you need to be able to recite them come exam time.

Who is at high risk of fat embolism?

This is broken down into two categories - 'those having their bones smashed about', and 'others'

Trauma and orthopaedics

- Long bone fractures - especially if multiple

- Pelvic fractures

- Orthopaedic surgery

Others

- Liposuction

- Severe burns

- Substantial soft tissue injuries

- Bone marrow harvesting

- Bone marrow transplant

- Diabetes

- Pancreatitis

- Total parenteral nutrition

- Steroids

- Sickle cell

- Fatty liver disease

- Osteomyelitis

- Bone tumor lysis

- Hepatic necrosis and fatty liver

How to diagnose it

Fat embolism syndrome often ends up being a bit of a diagnosis of exclusion with an enormous differential diagnosis, as there isn't a definitive test for it and it can be rather insidious in its presentation.

You have three options when it comes to diagnosis:

- Gurd criteria

- Schonfeld criteria

- Lindeque criteria

Of the three, the Gurd criteria are probably the highest yield to know.

Describe Gurd's criteria for fat embolism syndrome

To diagnose fat embolism syndrome, at least one major and four minor criteria must be present

Major

- Petechial rash

- Hypoxaemia

- Neurological disturbance

- Pulmonary oedema

Minor

- Temperature greater than 38.5°C

- Tachycardia greater than 110 bpm

- Evidence of myocardial ischaemia

- Retinal emboli on fundoscopy

- Sudden unexplained thrombocytopenia or anaemia

- Raised ESR

- Lipouria

- Fat in sputum

What do I do about it?

As with many things in our job, the best thing to do is prevent it happening in the first place.

How to prevent fat embolism syndrome

- Early immobilisation of fracture and early operative fixation

This is by far and away the most important one, so if you're only going to say one thing, make it that.

Other helpful things include:

- Avoiding intramedullary nailing

- Drilling vent holes

This seems logical - anything that helps to reduce intramedullary pressure during the operation is likely to help reduce the incidence of fat embolisation from the medulla - much like in bone cement syndrome.

But good luck trying to tell an orthopod what to do with their tools.

When you can't prevent it

Like the diligent anaesthetist that you are, you're going to do what you always do:

- Mute the alarms

- Give lots of oxygen

- Call for help

- Check that the alarms represent a genuine patient problem and not an equipment issue

- ABCDE and all that

- Focus on cardiorespiratory resuscitation to the very best of your ability, using fluids and pressors as you feel best suits the patient's requirements

And of course, you should say all this in the exam, but if you're asked for resuscitative targets specific to fat embolism syndrome then mention the following:

- Immobilise the fracture (you probably won't be doing this bit)

- Oxygenation and lung protective ventilation

- Avoid hypovolaemia

- DVT and ulcer prophylaxis

Things that probably don't help

- Steroids were thought to reduce the risk of fat embolism but we now think that they don't

- Heparin was thought to stimulate lipase activity and help clear fat from the blood, but now we think it doesn't

- Some people use albumin because theoretically it binds to free fatty acids - we'll let you decide.

You either like albumin or you don't and nothing we write is going to change your mind.

Are they gonna make it doc?

Probably.

Given its varied presentation and severity, as well as the fact it usually happens around the same time as another substantial trauma, procedure or comorbidity, it's tricky to ascertain exactly how bad for you fat embolism syndrome is.

In it's worst (or fulminant) form, where you see acute respiratory failure and cor pulmonale leading to cardiac arrest, it can be fatal within a matter of minutes to hours, but this is relatively rare.

Generally patients do get better, but it takes time, with symptoms improving over a matter of days to a few weeks. The neurological sequelae can persist, depending on their severity and why they occurred (acute hypoxia vs severe cerebral oedema etc).

Even if you end up developing ARDS, however, you're probably going to be okay within the year.

Useful Tweets and Resources

#Chestrad - fat embolism syndrome 🫁 From @StefanTigges pic.twitter.com/oCwd6LoRJe

— The Innovation | Medicine (@Innov_Medicine) December 14, 2022

Here's a cool case from emDOCs

References and Further Reading

Primary FRCA Toolkit

While this subject is largely the remit of the Final FRCA examination, up to 20% of the exam can cover Primary material, so don't get caught out!

Members receive 60% discount off the FRCA Primary Toolkit. If you have previously purchased a toolkit at full price, please email anaestheasier@gmail.com for a retrospective discount.

Discount is applied as 6 months free membership - please don't hesitate to email Anaestheasier@gmail.com if you have any questions!