Ether, Enflurane and Explosions

We recently discovered the fabulously diligent work done by Drs Whereat and Lewis over at Dr Gas and felt compelled to spread their efforts to our own audience so that you too may enjoy the fruits of their labour.

As always - no sponsorship, no advertising, just recommending great stuff that we find online.

They have also graciously given us permission to share part of an example post of theirs to give you a taster of what you can expect from their site and podcast.

Everything you read here is their work, formatted slightly to fit our vibe - enjoy!

A spot of history

Ether (or perhaps Aether) was first distilled around 1540(!) by Valerius Cordus, with some jiggery pokery involving gourds, wine, sulphuric acid and some clever distillation.

Ether's first use as a surgical anesthetic was by a GP Dr. Crawford W. Long on March 30, 1842, in Georgia, used to remove a neck tumour from a boy, James Venable.

Dr Long’s use was expectedly not noticed by the public, he didn’t publish, and Twitter was yet to exist.

He had been using the Ether for a laugh or two with the local folks where he noticed people sustaining non painful injuries.

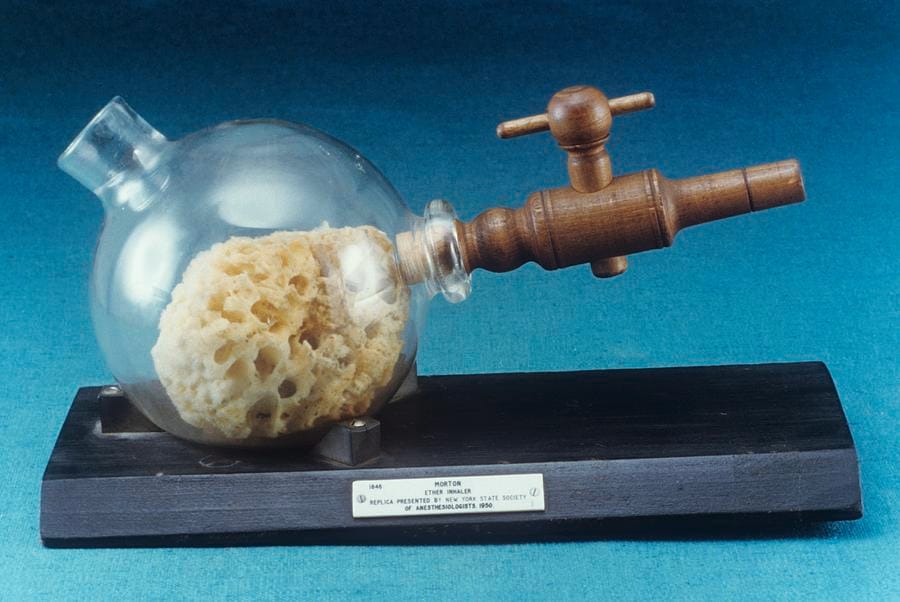

Four years later a public demonstration introduced ether anaesthesia to the world, performed by William T.G. Morton at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston on October 16, 1846 for the painless removal of a neck lesion from Edward Abbott.

Morton’s public demonstration of painless surgery sparked rapid adoption of ether.

Prior to this use, it had been administered via teapots in a clinic in Bristol for general ailments, and nitrous oxide was also noted at the time to be an amusing pneumatic to inhale.

Ether Pharmacology

- Name - Ether

- Class - Ether anaesthetic agent

- Chemical make up - (CH3CH2)2O

- Colour/appearance - Colourless liquid

- Flammable - and explosive

- Molecular weight - 74 g/mol

- Boiling point - 35°C

- Saturated Vapour Pressure @ 20°C - 56.7 kPa

- MAC50 - 1.92%

- Blood:Gas Solubility - 12

- Oil:Gas Solubility - 65

How to make it

- Mix sulphuric acid with a nice bottle of Pinot Noir

- Hollow out a gourd or two for fractional distillation

- Follow all the other steps of Williamson ether synthesis

- Store in sealed teapot

What About Enflurane?

- Devised in 1963

- Clear and colourless non-flammable liquid

- Anaesthesia is at 1.6% MAC

- CVS effects of Enflurane include a tachycardia, negative inotropy and coronary and general artery vasodilation

- RS effects include, Bronchodilation and significant Resp depression

- CNS wise, Enflurane can induce seizures, and increases ICP and cerebral blood flow

- It is 2.4% metabolised in the liver

- A further 2.4% is excreted via urine, sweat, faeces and the rest via exhalation

Through the Fire and Flames, and on to Explosions.

We’re going to go through managing an airway fire. Then we shall talk about explosions.

Why?

Because there is an BJA article that was probably quite fun to write that handles explosions, I’ll link to it in the references. Also because I found a book called Physics for the Anaesthetist, including a section on explosions in a charity shop a number of years ago . It actually transpires that when I’ve looked at this book properly, it was written by Sir Robert Macintosh and some colleagues.

Macintosh of MacBlade Fame + all his other exploits at the time.

Fortunately, we live in a world where in-theatre explosions are much less likely. This is because, as we’ve mentioned earlier in the show, there aren’t as many explosive gases knocking around and safety practices are fairly maximal.

Tis certainly important for us to know about how to deal with a fire. That could be an airway fire, or it could be a fire on the patient.

If the surgeons have been a bit liberal with their chlorhexidine, failing to mop it up, or failed to allow it to fully evaporate, there is a problem. The alcohol content of chlorhexidine antiseptic is really high, you can end up with an invisible fire because of the nature of the flame, alcohol emits little visible light spectrum when combusting.

And I think it’s quite interesting to understand a bit more about what an explosion is. We need to define or die a number of things and appreciate how flames behave through flammable materials in order to differentiate What? What a flame is, what deflagration is, and what an explosion is.

Definitions or Death

Flame

- A hot glowing body of ignited gas that is generated by something on fire – combustions that produce light cause a flame

Cold flame reactions

- An oxidation reaction of a mixture that will only sustain whilst there is a source of heat energy supplied

Deflagration

- Burn or cause to burn away with a sudden flame and rapid, sharp combustion (in a controlled system)

Conflagration

- An extensive fire which destroys a great deal of land or property, think wild fire, (con- as a prefix means with, or thoroughly)

Combustion

- A rapid, exothermic redox reaction (oxidation) between a fuel and an oxidant, usually oxygen

- That releases significant energy as heat and light

- Often producing oxides, carbon dioxide, and water as products

Flash point

- A property of a liquid fuel, whereby the temperature of a volatile liquid fuel will give a flash of flame across its surface when a flame is passed across it

- Imagine, very hot petrol, doing lots of vapourising, would probably burn raucously

- Whereas very cold petrol, might only vaporise a little, and have a more sedentary flame skip across its surface

Explosion

- Really anything that achieves a volume of expanding gas in very short time frames

- The shorter the time frame, the more boom there is

Sub Types of Explosion

- Mechanical – Over loading something with compressed air, if you heated a VIE and closed the release valves you would eventually cause a boom as all that liquid o2 wants to be a gas 861x the size

- Nuclear – rapid release of huge quantities of energy causing heat expansion of the gas around the explosion alongside all the rest of it

- Chemical - detonating types like TNT/’C4’/Dynamite AKA High Explosives and deflagrating types, so called low explosives

Shock Wave

- A sharp change of pressure in a narrow region travelling through a medium, especially air, caused by explosion or by a body moving faster than sound waves through that medium

Detonation is combustion of a substance which is initiated suddenly and propagates extremely rapidly, giving rise to a shock wave.

For a Fire to Get 11A* at GCSE it generally requires the right combination of:

Heat source

A spark, or a flame or sufficient compression of a gas. Or anything that delivers concentrated heat (a magnifying glass, Laser, Electrocautery) or in true NHS fashion, everyone knows of a slightly dodgy electrical socket with some tape over it saying do not use, nor should you toast bread using open flame or modern toasting devices as these are notoriously sparky and will be sufficient for deflagrations.

Oxidisers

Generally this is oxygen, as a fraction in air. It can also, in the anaesthesia setting be nitrous oxide or the nitric oxide of hydrogen peroxide.

Fuel

Material that contains molecules that will reconfigure if oxidised into a lower energy state – releasing heat energy.

Peri-operative fuel sources include bowel gas, surgical prep, drapes that melt, burn and cook when the laparoscope that’s been set to 9000 lumens are left pointing at them and probably many other things.

Mitigating Fire Risk

Less exciting but still very important here - tactics to mitigate the potential for fire.

- Be as cheap as you can with oxygen, and don’t leave a face mask blowing under the blankets in Resus, nasal specs under the sheets is another thing, and static pings from a NHS blanket is not unheard of.

- Unplug the nitrous from the anaesthetic machine and throw the piping out, (or if feeling less maniacal / extreme, just don’t use nitrous.)

- Fire safety plan when using lasers,

- Keeping an eye on the sloshing of high alcohol solutions.

- Being cautious with igniting body hair.

- Regular PAT testing of electrical kit, anything that you touch that tingles needs to be turned off. Isolated from any staff thinking about switching it on again

- Don’t grease your BODOK seals, even if there is a tank/yoke leak. The compression effect of tank pressure on the greased seal can lead to flames from the back of your anaesthetic machine

However cool it may sound to have a backfiring anaesthetic machine, it is in fact very hot and quite precarious, and may ignite all the other stuff dangling on the back of the machine.

For more fire safety learning, do attend induction, and check out the BJA article, as whilst I do jest, fire is exceedingly, devastatingly bad in a hospital packed densely with unwell people who cant evacuate in an orderly manner.

Handling An Airway Fire

First step is actually spotting one, there may be a flash, a pop or a funky smell, +/- smoke.

Second step is hollering FIRE

And in a co-ordinated manner:

- Stop Ventilating,

- Deflate if possible and remove airway devices

- Slosh copious saline into the airway – a jug of water must always be available in surgeries with fire risk

- Surgeon should remove any remaining debris once saline is in (any plastic will have cooled down)

- Ventilation should be resumed, with recommendations to use low fiO2 fractions or room air via an AMBU bag.

If the fire is instead not contained and spreading over the patient, then a CO2 extinguisher, should be used if safe and a fire alarm certainly sounded.

If control was attained, then the airways need to be inspected for injuries, (bronchoscopy) further airway toilet as needed, and a plan formulated.

There is potential for airway and lung parenchymal injury, and as such, keeping the patient sedated and intubated for a period of observation is necessary to observe for ARDS / gas exchange complications.

Sources of Ignition

Autoxidation

Once upon a time, Ether explosions came about due to chemical instability introduced by exposure to light and air, whereby peroxides (hydrogen peroxide for example) were formed in the solution.

This situation is very labile, and act like detonators in high explosive mixes (High explosives often need fairly significant energy to trigger their reaction).

This ‘self’ creation of a detonator is called autoxidation, and accidental shaking of a sample of ether exposed to light in a lab has led to explosions, introducing anti-oxidants to your ether solution, and storing it in the dark, mitigates this.

Spontaneous Ignition

If a particular gas mix, is heated to a particular temperature, it will undergo simultaneous combustion throughout the whole mixture.

Somes gases burn simply when warm enough, others if allowed to shift towards room temperature will spontaneously combust. Highly precarious things, thankfully there are very few that do this. All gas mixes generally have an auto-ignition temperature.

As you would expect, most things don’t spontaneously erupt into flames at general atmospheric temps, because otherwise our planet would be much less likely to support life as we know it!

Wood will auto ignite at 300°C and isopropyl alcohol at 399°C

Sources of Local ignition – more relevant to the jobbing gas slingers of the modern age

- Open Flames – there are very few theatres which now have an open coal fire for warmth

- Cigarettes ……

- Laparoscopes with their high intensity light sources burning drapes (seen it)

- Diathermy

- Arcs from faulty switches

- Static build ups – only occur in non-earthed or poorly conductive materials which are unable to dissipate their -ve charge.

Mitigations for Ignition sources

- Maintaining a degree of humidity, leads to surfaces being a tad moist, bolstering their conductivity and hence static potential differences dissipate before they can be come dangerously charged.

- Using materials that are more conductive, ie, rubber that is altered to be a less effective electrical insulator.

Explosives in Anaesthesia

The explosions that were seen in anaesthesia often weren’t the absolute fastest, like dynamite / TNT. Instead tending to be a mixture that might be burning its way through a mix journeying along a tube, vide infra.

There have been a few other explosives used in and around anaesthesia:

- The original ether, aka diethyl ether, had a friend called di-vinyl ether, which was more boomy and combustible again

- Ethyl chloride which is used for cold sprays testing spinals in places that haven’t just progressed to a bit of metal on a stick in a fridge. Ethyl chloride in oxygen produces an explosive mixture with a range of 4 to 67%, which is broad. Whereas in air… 3.8 to 15% concentrations will explode.

- Cyclopropane, which was once upon a time used, Mixed with oxygen, a range of 2.5 to 60% cyclopropane to oxygen would result in booms and deflagrations, whereas cyclopropane and air will only deflagrate.

- Nitrous oxide supports combustion and it burns hotter compared to a solitary oxygen mix.

- As the nitrous in a mix is heated, the oxygen is liberated, providing more than the 21% available in air.

- Hence its use to jazz up engines in need for speed underground 2

Combustion Reactions for the Jobbing anaesthetist

A representation of a simple combustion reaction would look like:

Reactants (Gases A + B) >>> Heat Added >> Chemical rearrangement >> Products (Gases C+D etc) +/- Heat +/- Photons

Generally, you need to deliver energy to break a bond, when you make a bond, further energy is released.

This is the activation energy of a reaction, which needs to be added to the system for a conformational change in the molecules of that system to occur leading to new chemical arrangements that will either release or absorb energy, depending on the nature of the reaction.

And in most systems, these reactions will go from a less stable to a more stable set of molecules when they oxidise i.e. from more reactive to less reactive.

An Example of Combustion we are all familiar with

A better example of this is wood.

When you burn wood you’re not just burning the cellulose of the cells of the wood but the saps, the sugars etc. These all burn at different temperatures. There are varying amounts of it within it and often they’re shifted into their volatile or gas phase before being ignited.

If your fire lacks heat energy, you’ll often see a lot more smoke, and that’s because you are incompletely combusting the generated gases and vapours of volatile things coming out of the wood.

Whereas if you can get sufficient heat in your fire, you end up with much cleaner smoke-free flame as everything is combusted. As you might expect, if you successfully and entirely combust all of the material, you will generate more heat as opposed to wasting stuff.

That’s why wood-burning stoves are designed in a manner that A contains the heat, B will provide sufficient oxygen to the materials in order to combust them. Otherwise the wood-burning stove furs up your flue or chimney with non-combusted but combustible materials. If you then go and actually get a rip-roaring fire going in there, you will ignite those materials now deposited up your flue. Remember they deposit as they cool, they’re more likely to stick to the flue. And therefore you can get a flue fire.

The heat released from a reaction will go on and increase the rate of that reaction as long as the heat is contained and isn’t being freely dissipated.

Factors Influencing Reaction Rates

- Fuel Mix

- Heat gain / Loss in a system

- Physical environment enclosing (or not enclosing) the reaction.

Fuel Mixtures

In a perfect world 10 x A + 10 x B >>>>> 10 x C and 10 x D + Heat + Light

This would be a stoichiometric mixture. Its reaction rate would not be constrained by the available substrates for the reaction.

But if you swing to either side of this stoichiometric mix, you either end up with a rich mixture or a lean mixture. You might have come across this if any of you folks are motorbike aficionados. You can fiddle around with your carburettor and provide your engine with more or less fuel.

The more you swing towards leaner or richer mixtures, the slower the rate of reaction will become, noting again that the stoichiometric mixture is the most rapid to react.

Now, depending on what you have mixed in this tube dictates that reaction speed, and whether or not the heat generated by the reaction is sufficient to maintain that wave front of flame.

Heat Gain / loss

If losses are too high, then you have an imbalance that leads to failure of propagation of that burning wave front through your tube. Vide infra

- If there are non-combustible gases in this system, those gases will get heated unnecessarily. For example, if you’ve got nitrogen in this tube as well. its inert, and not involved in the reaction, but it’s going to soak up some of the heat generated,

- Heat may be conducted or radiated out depending on the material the system is made of.

- If the gas is humid, i.e. there’s water vapour again, that’s another thing that can get heated.

- And equally the gases of combustion, i.e. the resul tant reactant products themselves, are going to be warmed, but not useful for further reactions.

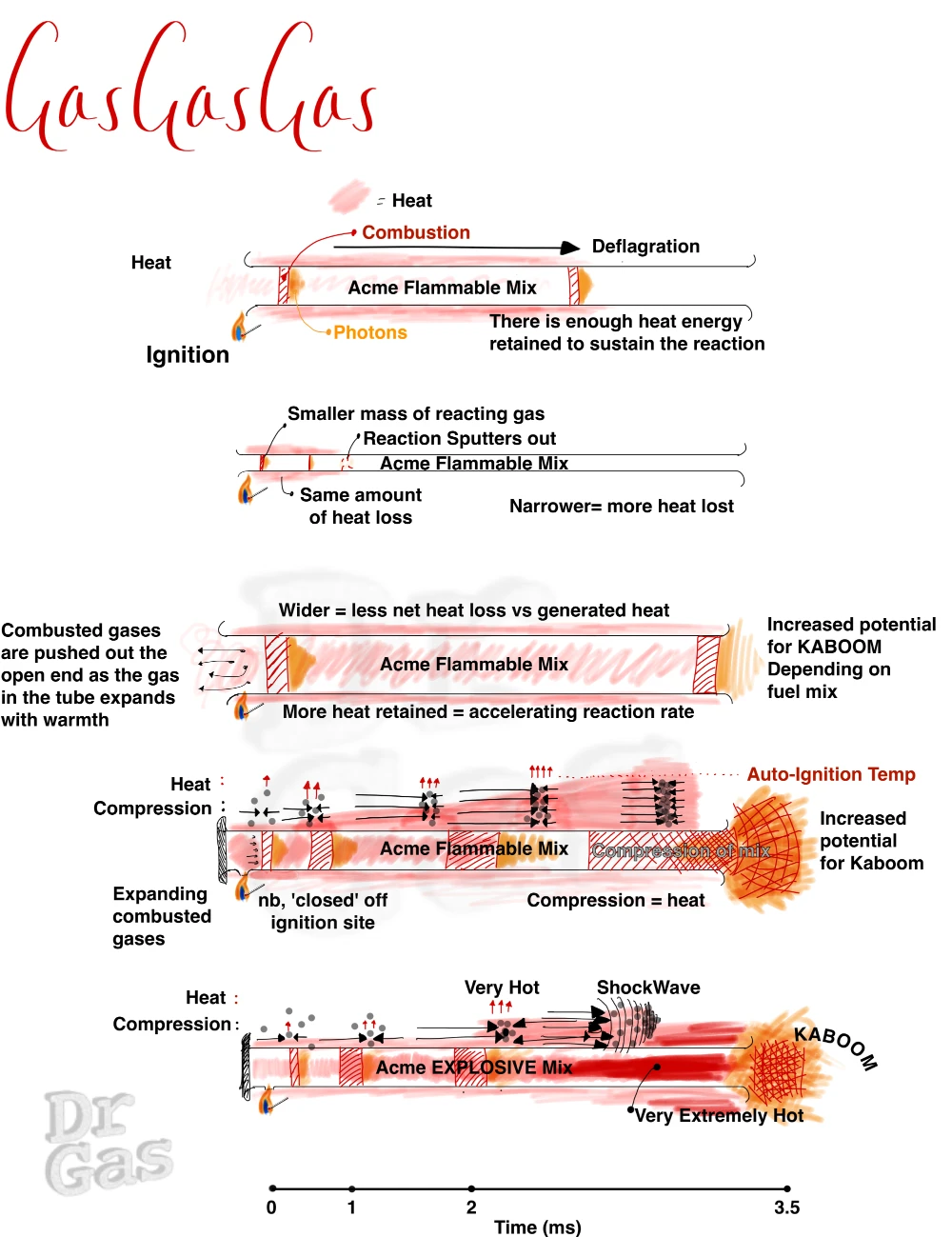

The Behaviour of a Combusting ‘wave front’ within a system

As anaesthetists, we are somewhat interested in deflagrations and explosions that might happen within our ventilatory apparatus. i.e. in tubes.

Imagine an open ended tube, with a flammable gas mixture within it. We introduce a heat source at one end (A).

Four outcomes may occur

- The flame sputters and fails as there is insufficient heat to maintain combustion

- The flame tracks from A though to B speeding up a bit as it goes

- The ignition near immediately causes a burst of flame and heat from each end of the open tube

- For the astute, a fourth option would be, the mix fails to ignite

As long as that mix can self-maintain its combusion(reaction) with the heat it generates, you will end up with a wave of flame transiting that tube from one side to the other, from A to B.

If you were to start the reation from the middle, it would propagate in both directions,

The speed at which it transits from A to B is directly related to the speed of the reaction.

The flame that you see in this tube is that wave front where the oxidation reaction is actually taking place, generating photons.

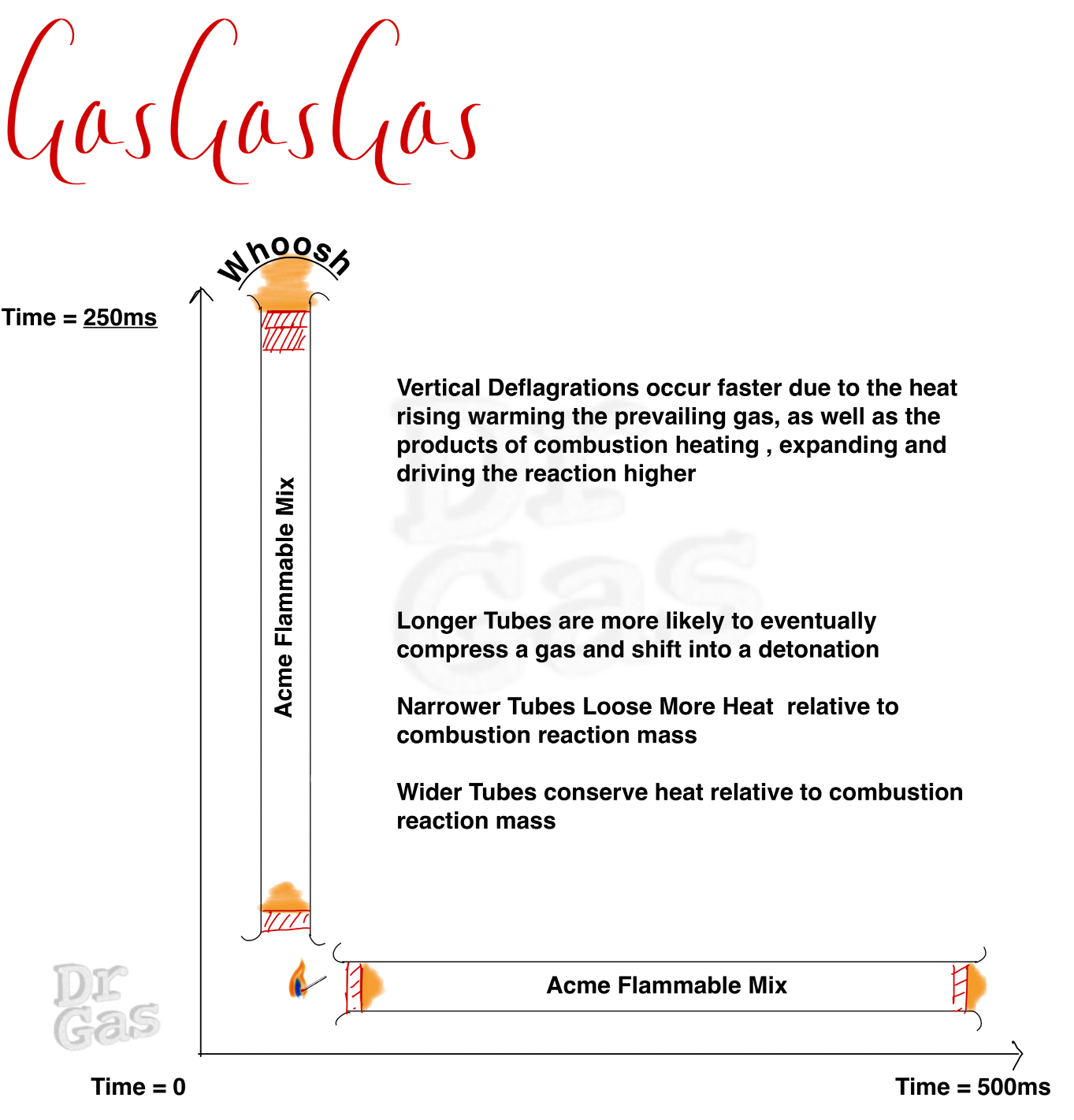

What about different tubes?

We need to think about a few different permutations of this tube. My original tube has a hole at both ends. But what if you have a closed end and you start your ignition from that closed internal end, the nature of the expansion of those gases and the heat agenerated will go in a single direction, it doesn’t escape out in both directions. This can lead to an expanding and speeding up wavefront as you heat the reacting . If your tube is in a vertical position and you light it from the top, The propagation of that flame downwards is quite slow, as a lot of heat is lost out of the top. Whereas if you start that fire at the bottom, you have a much more rapid reaction rate.

So, now we know that if we start a fire in a tube, it propagates along that tube. We know that there are rich mixtures, lean mixtures, and stoichiometric mixtures. And by that virtue, we need to consider that at some point, with the correct conditions, our propagating flame (deflagrating) down our tube will turn into an explosion down our tube. This is generally when we are in that middle stoichiometric ground, with a mix that can react fast enough to tip into detonation. Bear in mind that an O2:fuel mix has a much broader range of boom than an air:fuel mix, noting, only some air fuel mixes will detonate.

Implications of fire in a breathing circuit

Deflagrations in a circuit may progress all the way to the alveolus, but in modern circuits, this flaming wave font might be held up at the HME with a much moister environment within it and on the opposing side of it, demanding more of the heat energy of the reaction to continue.

Detonation within a breathing circuit doesn’t lead to just airway burns of the patient but that pressure spike in the circuit can lead to blast injuries of the lungs as well much like the concerns we have for soldiers involved in blasts especially in contained places or of significant kinetic energy they can end up with blast lung which is a life-threatening issue that looks a bit like ARDS.

Time for an analogy

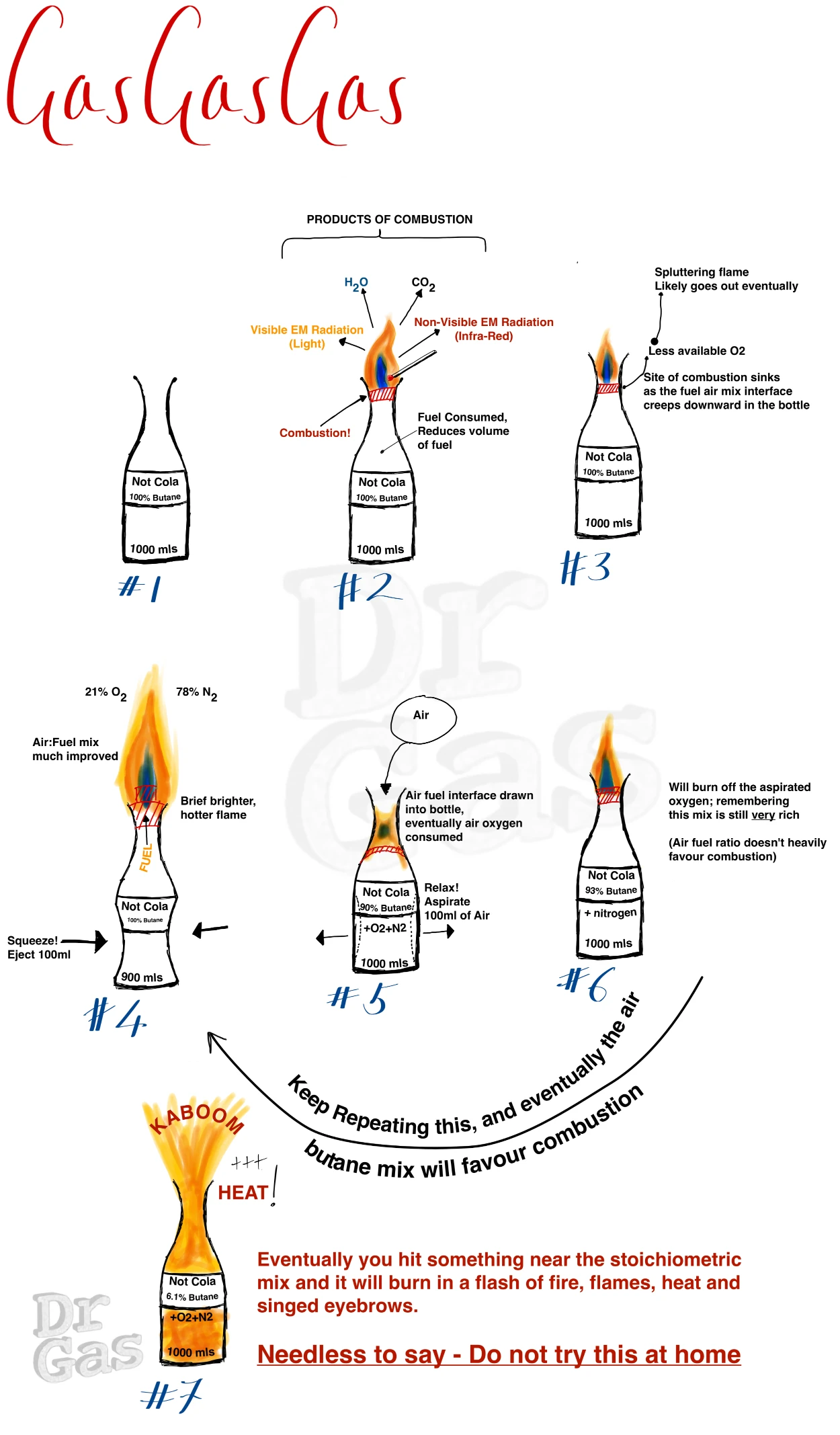

As a young idiot, I took a 1 litre Coca-cola bottle, drank the Coca-Cola, and then filled that Coca-Cola bottle with butane from a lighter.

I then lit that.

It burned slowly with a flame from the end, and if I squeezed the bottle and ejected some of the butane, it would puff out a little fireball, which all was fun.

Otherwise it went out.

As I was fiddling around trying to re-ignite the mix, I squeezed the bottle and aspirated a load of air inside it. That aspirated air mixed with butane, creating a now flammable butane:air mixture and this system actually blasted flames out of the end of the coke bottle all over my hand and blistered the crap out of my hand.

Naturally, I did not own up to this.

My hand recovered within a week and a half, the blisters burst. Very painful, but demonstrates that that was initially a rich mixture. It was just about burning when some of the butane escaped the end of that bottle mixed itself down into a flammable mixture.

Eventually it hit a sweet spot where I’d inadvertently created a near stoichiometric mixture that went vwoomph in a flash of burning that was much hotter and sizzled me.

After that I was much more careful to point the bottle away from myself, I remained an idiot.

Don’t try it at home folks!

Hope you have enjoyed this, and if you’ve made it to the end, 10 points to Gryffindor!

Here's their brilliant podcast

Here's their fabulous website

Here are our other history posts