Cell Salvage

Take home messages

- Salvaged blood is only red blood cells

- Cell salvage can dramatically reduce the need for allogenic blood

- It takes time to set up and isn't without its complications

Podcast episode

Better out than in

Except for blood.

Blood is renowned for being very much better on the inside, and if it can be inside some sort of blood vessel then better still.

Occasionally, however, it falls out and despite our best attempts to stop it doing so, we're left with only one option - put more in.

You can faff about with fluid boluses, tranexamic acid and whatnot all you like, but at some point you just have to replace blood with blood.

Now you can either give the patient allogenic blood (from someone else), or you could employ cell salvage.

Cell salvage is a nifty technique that involves hoovering up the patient's own spilt blood (from the patient, not the floor or the bin) before filtering and processing it such that it is safe to re-infuse from whence it came.

Ideally after haemostasis has been achieved, otherwise it'll just be running laps.

Use it or lose it

The key, as with any piece of expensive machinery, is to actually use it. Cell salvage is not cheap, and only really becomes cost effective if it gets moderately regular use (and is used properly).

A unit of donated blood costs £135 or so once it's been fully processed and is sat ready to transfuse.

Using cell salvage for a whole surgical case costs between £70 and £200 depending on how much use it gets and what disposables are consumed. The more it gets used, the cheaper it is per case.

So it doesn't take much mental arithmetic to work out that using cell salvage once a year for a patient that only needs a single unit top up is not hugely cost effective, while a cardiothoracics centre using it daily for cases that would otherwise end up requiring multiple donor transfusions is likely to see substantial benefit from their original investment.

A Spot of History

The first documented case of attempting to return our beloved DO2 doughnuts back into a patient is from way back in 1818. A gynaecologist by the name of Blundell took the blood-soaked gauze, rinsed it out in saline and infused the resulting mixture straight back into the patient.

He attempted this many times.

Unsurprisingly it didn't work all too well on any of the occasions - with a disastrously high mortality rate - an 'A for effort, D for attainment' kind of situation.

By the time 1931 drifted around, blood from haemothoraces was being pumped straight back into the circulation, with mixed results, and it wasn't until 1943 when Arnold Griswald produced the first dedicated device for auto-transfusing of salvaged blood.

This device would suction up the spilt blood and filter it before it was reintroduced from whence it came, and formed the basis of the machines that we see today.

Unfortunately the complication rate remained very high until relatively recently.

What are the complications of cell salvage?

- Haemolysis

- Venous air embolism

- Coagulopathy

- Infection

- Electrolyte imbalance

- Febrile reactions and hypotension

- Transmission of infection

Why not just transfuse?

Good question, and a lot of the time the answer is we do.

Transfusing blood is a very effective but distinctly suboptimal way of keeping someone alive when you think about it.

In order of preference, the options would probably be:

- Stop the bleeding way before they become symptomatically anaemic

- Stop the bleeding in time that with a bit of fluid and iron the patient will be right as rain in a few weeks

- Shlorp (yes, shlorp) up all of the patient's spilt blood and give it back to them

- Give them someone else's blood

Red cells are red cells

We don't ask for much, us anaesthetists, other than a steady supply of oxygen to the brain and vital organs. Give us that and we can happily cope with some hypotension, tricky ventilatory pressures or even the lack of a chair.

So when it comes to losing red cells en masse, then it makes sense to throw in a few more to maintain that highway of DO2 to the cortex, however it is not without its risks when you've had to get those red cells from somebody else.

What are the complications of allogenic blood transfusion?

- Febrile reactions

- Anaphylaxis

- Haemolysis

- Transfusion associated circulatory overload (TACO)

- Transfusion associated lung injury (TRALI)

- Transmission of infection

- Immunosuppression

Donated red cells do deliver oxygen better than normal saline, but only if warmed up appropriately and not nearly as well as native blood:

- They lose their shape and become less flexible for squeezing down narrow capillaries

- They have essentially zero 2,3-DPG or ATP, meaning they're aren't all that generous when it comes to offloading O2 to the tissues

- They can trigger a whole host of reactions and also seem to cause substantial immunosuppression in the recipient

Not to mention that some patients will flat out refuse to allow you to infuse another person's blood into their veins.

This is where cell salvage seems to come into its own, as the salvaged cells retain their shape and flexibility, they have much more 2,3-DPG and ATP, and they don't seem to cause nearly the same level of host reactions as donor blood.

How does it work?

The principles of red cell salvage are relatively simple.

Take the blood, clean it, and put it back.

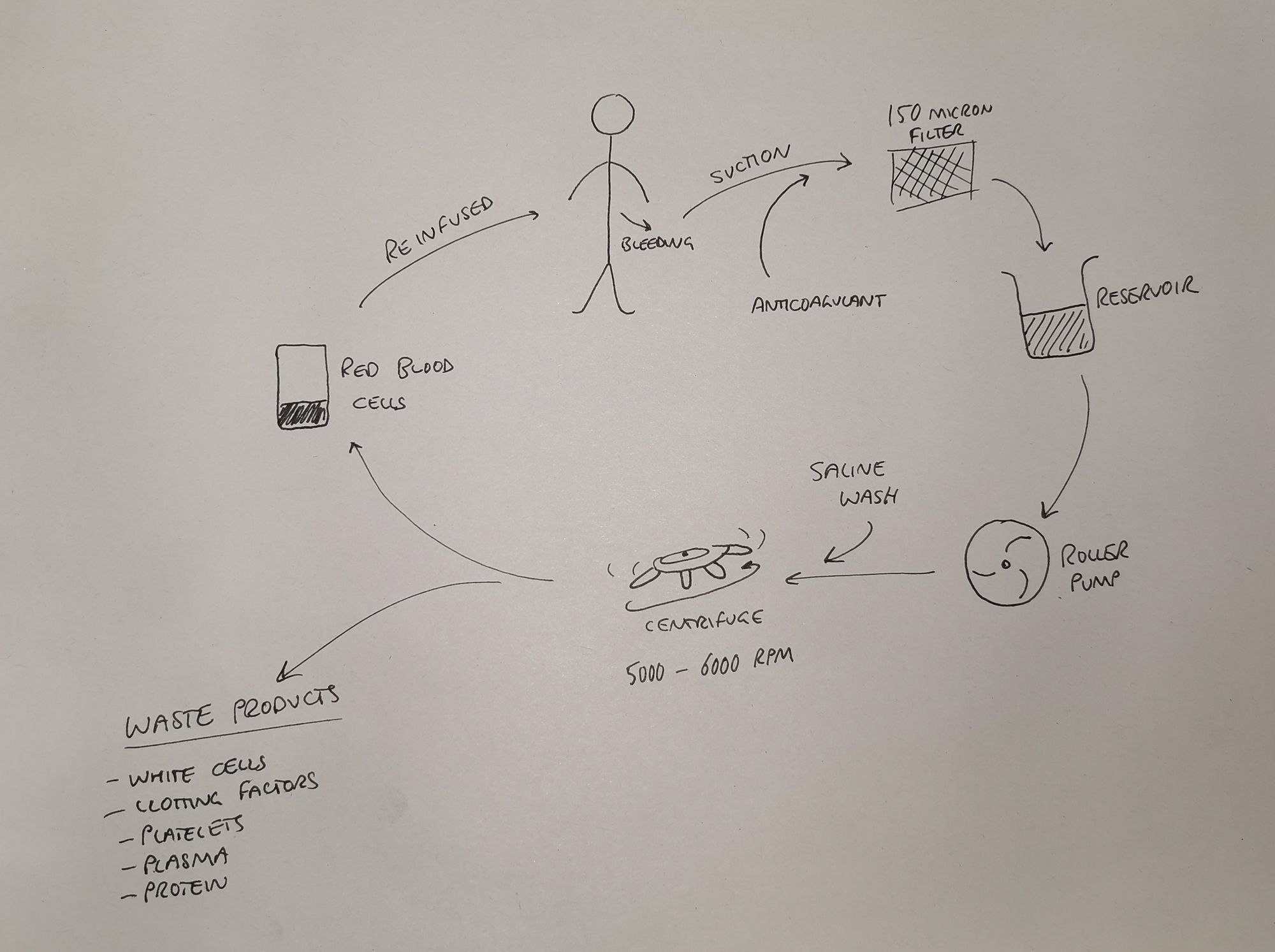

The steps of cell salvage

- Spilt blood is suctioned from operative field, or washed from used swabs

- It is anticoagulated and filtered (150 micron filter)

- Then it is centrifuged to separate the red blood cells out (5600 rpm)

- Red blood cells are washed with normal saline

- A solution of erythrocytes in normal saline (haematocrit about 0.6) is then ready for re-infusion

The other blood components such as plasma, proteins, leukocytes, platelets etc are discarded, so remember you're not returning whole blood to the patient.

Collection

Collecting the blood - much like spilling it in the first place - is invariably the remit of the surgical team.

Generally speaking as the anaesthetist you won't get involved in collecting the blood however it's always good to look keen and offer to help I suppose.

The aim is to retrieve as much blood, and as little other stuff*, as possible.

*other stuff including

- Bone

- Faeces

- Cement

- Pus

- Urine

- Chlorhexidine

- Glue

The collection process usually employs a dedicated suction instrument, separate from the standard surgical suction.

- The standard surgical suction's role is to optimise the surgeon's view by violently removing anything with a sufficiently small diameter

- The cell saver suction's role is to gently encourage red blood cells into the salvage machine, without destroying them or upsetting them too much

There is also the manual method of washing bloody swabs in heparinised saline, which can then be suctioned (gently) as well.

The blood is then quickly anticoagulated using heparin or citrate, to prevent it doing what it does best and rendering the whole process completely useless.

Separation and Washing

You don't really need to know much more detail than "The blood components are separated out, and everything but the red cells is thrown away" but you might get a pesky exam question asking for a bit more specific information about the separation process, so here goes.

Blood can be separated out via one of three mechanisms, all of which involve some sort of centrifuge:

Fixed bowl system

- Blood is collected into a rotating, conical shaped bowl

- The bowl fills as it spins, so the blood naturally separates according to density

- The waste is spun off and the red cells remain in the bowl

- Once a set amount of red cells have accumulated the machine will start washing

It's called a 'fixed' system because it has to collect a set amount of red cells before the washing process begins

Variable volume disk system

- Similar system to the fixed bowl, however it has a specific diaphragm made of silicon

- This allows the washing process to occur at a variety of red blood cell volumes, making it more useful if only a small amount of blood is collected

Continuous rotary system

- As the name suggests, there is a continuous process of waste product removal, red cell concentration and washing

- This allows smaller volumes of blood to be infused more frequently

After collection and separation, the erythrocyte soup that remains is washed in saline to remove any remaining contaminants and free haemoglobin.

Reinfusion

Usually if you're employing cell salvage then the patient needs the blood back fairly sharpish, so you're probably going to be reinfusing as soon as it's been processed and made available by the machine.

The time limit is essentially six hours before the blood becomes substantially less effective at carrying oxygen.

It should never be given under any sort of pressure greater than gravity alone - for risk of venous air embolism, and the cannula and giving set should ideally be dedicated only to infusing blood, but certainly at least thoroughly flushed before hand.

Who can't have it?

It has been claimed that sepsis and malignancy represent contraindications to cell salvage however this is very much a relative rather than absolute issue - if it's in the patient's best interests then it's not off the table in these cases.

Jehovah's Witnesses

Genesis 9:4, Leviticus 17:10, and Acts 15:29 all forbid human consumption of blood in any form.

Jehovah's Witnesses need thorough councelling on the exact circumstances under which they would not accept a blood transfusion, as it may depend on how life-threatening the situation is.

If a patient will not accept a blood transfusion under any circumstances, they may well accept cell salvage, and this may need explaining to ensure they understand the process.

I have looked after a patient who refused all and any blood that was either from another person or that had left her body, but after discussing the process of cell salvage, we agreed that if there was a closed circuit from body to suction to salvage to reinfusion then she would accept it.

She ended up receiving over 500ml of her own red cells, with a post-operative haemoglobin of 85, so it was definitely worth the long discussion.

What about sepsis?

Long story short, a patient with sepsis and significant blood loss is likely to do better if that blood is returned to their already stressed cardiovascular system.

Yes, avoid suctioning gallons of pus into the cell salvage machine, and yes they're likely to be more susceptible to cardiovascular instability, but in reality, if you use the suction properly, and a leucocyte depleting filter where necessary, there isn't any solid evidence to suggest that cell salvage makes the situation any worse.

Just make sure the patient's had a hefty dose of broad spectrum antibiotic.

What about cancer?

The thought process here is fairly simple - ideally don't suction up a whole bunch of cancer cells and flood them back into the circulation, because it might seed metastases.

This idea has largely been disproven and there is increasing support for the use of cell salvage in cancer surgery.

By being careful with how the blood is suctioned and using a leucocyte depletion filter the burden of malignant cells can be dramatically reduced.

Furthermore the evidence seems to suggest that patients with cancer often have malignant cells in the circulation already, and very few of these are actually capable of seeding a new metastasis. One would imagine cells that have just left the body, been slammed through a suction catheter, centrifuge, powerwash and then microfilter are probably less likely to be able to start a colony of their own, but I have no strong evidence to support this claim.

Even more furthermore, by reducing the need for allogenic transfusions, you also reduce the immunosuppressive effect of donor blood, and therefore give the patient a better chance of fighting off any further growth.

What about sickle cell?

Any patient with a haemoglobinopathy is going to have more difficulty with cell salvage, because the mechanical stress of being suctioned, filtered, washed, centrifuged and reinfused is rather full-on when your membranes are already fragile.

Salvaged cells are more likely to sickle, clump, precipitate or haemolyse and as a result, cell salvage is relatively contraindicated.

Bear in mind, also, that this cohort of patients may benefit from an allogenic transfusion because it will reduce the proportion of their circulating blood that is prone to sickling, thereby reducing the chance of a crisis rather than increasing it.

What about Orthopaedics?

- Cell salvage dramatically reduces the need for donor blood

- This is particularly true for pelvic and spinal surgery, as well as big joint revision cases

- Don't use it while cementing, okay to continue once cement set in place

- There is some query about whether there's a risk of metal fragments smaller than 40 microns are of any concern, so they just advise to be 'prudent' with washing and suctioning

What about obstetrics?

Again - if you've got a patient who is haemorrhaging and you have a cell salvage machine available, it might be a good idea to think about using it.

The current guidelines are frustratingly non-committal, with lots of 'needs to be decided on an indiviual basis, with the patient's risk factors taken into account' type statements as you would expect.

- The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists do support the use of cell salvage for caesarean sections - both elective and emergency

- The SALVO trial suggested that it doesn't seem to reduce the amount of donor blood given

- 2018 Association of Anaesthetists guidance is that it is not recommended routinely

- If it is used then it should be in the 'collect' mode only for women identified as anaemic preoperatively

- The nice cop-out statement of: Individualised risk/benefit needs to be assessed when making the decision

- Theoretically there's more risk of fat embolism or amniotic fluid embolism

- LDFs can reduce the risk of amniotic fluid embolism, but come with their own host of risks and complications so they end up not being used all that much

- Also increased risk of exposure to foetal blood, so UK guidelines state that Rhesus negative, non-sensitised mothers with Rhesus positive babies should get anti-D immunoglobulin within 72 hours of any cell salvage use

It's particularly useful in cardiothoracics

Cell salvage in cardiothoracic surgery

- Routine use of cell salvage in cardiac surgery decreases the need for donor blood transfusion by up to 40%

- It should only be used for significant blood loss, and after bypass

- This is because using it during bypass removes clotting factors and platelets, which would be preserved if the blood were suctioned directly in to the cardiotomy reservoir

A Free CRQ on Cell Salvage

Useful Tweets and Resources

References and Further Reading

Primary FRCA Toolkit

While this subject is largely the remit of the Final FRCA examination, up to 20% of the exam can cover Primary material, so don't get caught out!

Members receive 60% discount off the FRCA Primary Toolkit. If you have previously purchased a toolkit at full price, please email anaestheasier@gmail.com for a retrospective discount.

Discount is applied as 6 months free membership - please don't hesitate to email Anaestheasier@gmail.com if you have any questions!

Just a quick reminder that all information posted on Anaestheasier.com is for educational purposes only, and it does not constitute medical or clinical advice.