Applied Physiology for the Final SOE

This is a rapid review article for the Final SOE examination, discussing the use of arterial tourniquets during limb surgery.

Information for the candidate

You are anaesthetising a 65 year old woman with mild Raynaud's disease for a tibial nail, after she tripped on a curb and sustained a spiral fracture of her left distal tibia.

What pressure should the tourniquet be inflated to?

- For lower limb use double the systolic pressure up to 150 mmHg above systolic

- For upper limb use 50 mmHg above systolic

What are the indications for using an arterial tourniquet?

- Limb surgery requiring a bloodless field

- Intravenous regional anaesthesia

- Control of catastrophic haemorrhage from injured limb

What are the contraindications?

As always, divide into absolute and relative.

Absolute

- AV fistula

- Suspected DVT

- Concern about disseminating infection or malignancy

Relative

- Peripheral artery disease

- Significant crush injury

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Loss of skin integrity

- Sickle cell

- Raynaud's disease

What are the effects of tourniquet inflation?

This can be divided into local and systemic.

Local

- Muscle injury

- Nerve injury - particularly radial and sciatic

- Vascular injury

- Skin damage

Systemic

Cardiovascular

- Small increase in systemic vascular resistance

- Increase in venous return can theoretically cause fluid overload in cardiac patients

- Blood pressure and heart rate will increase with increasing duration of tourniquet time - this effect is reduced for lower limb tourniquets with spinal anaesthesia

Respiratory

- DVT and PE risk

Metabolic

- Anaerobic metabolism in the limb leads to accumulation of metabolic waste

- This can lead to acidosis

- Infection can theoretically be encouraged to spread by applying a tourniquet

Pain

- Due to a combination of direct pressure, acidosis and ischaemia

How long can a tourniquet be used for?

- 2 hours in an otherwise healthy patient

- Less for elderly or unwell patients

- If it's going to take longer then the tourniquet needs to be deflated for ten minutes after 1.5 hours to allow reperfusion

What are the effects of deflating the tourniquet?

Probably best to work through this in a chronological fashion.

- Tourniquet deflates, releasing arterial pressure and reducing systemic vascular resistance

- Blood flow is diverted to previously occluded limb

- Venous return to the heart transiently decreases, causing a drop in blood pressure and a compensatory tachycardia

- Cold blood full of metabolic waste is flushed (including lactate, CO2 and potassium) is flushed into the venous system, causing a transient and mild drop in core temperature

- Acidosis, hyperkalaemia and hypothermia can lead to arrhythmias and labile blood pressures in frailer patients or after a long tourniquet time

- The excess CO2 is delivered to the lungs, causing an increase in EtCO2

What are the complications of tourniquet use?

Complications are rare at around 0.04%, but can be significantly debilitating.

- Usually nerve injury is the issue

- Mostly this will resolve by itself within six months

- Higher risk with lower limb tourniquets than upper limb

- Bigger nerve = higher risk of compressive damage

- Esmarch bandages can be surprisingly powerful and cause nerve damage by generating upwards of 1000 mmHg of pressure

- Compartment syndrome and rhabdomyolysis are possible if there is significant oedema after reperfusion

- Skin injuries can occur if inappropriately applied

- Arterial injury is possible, especially in peripheral vascular disease

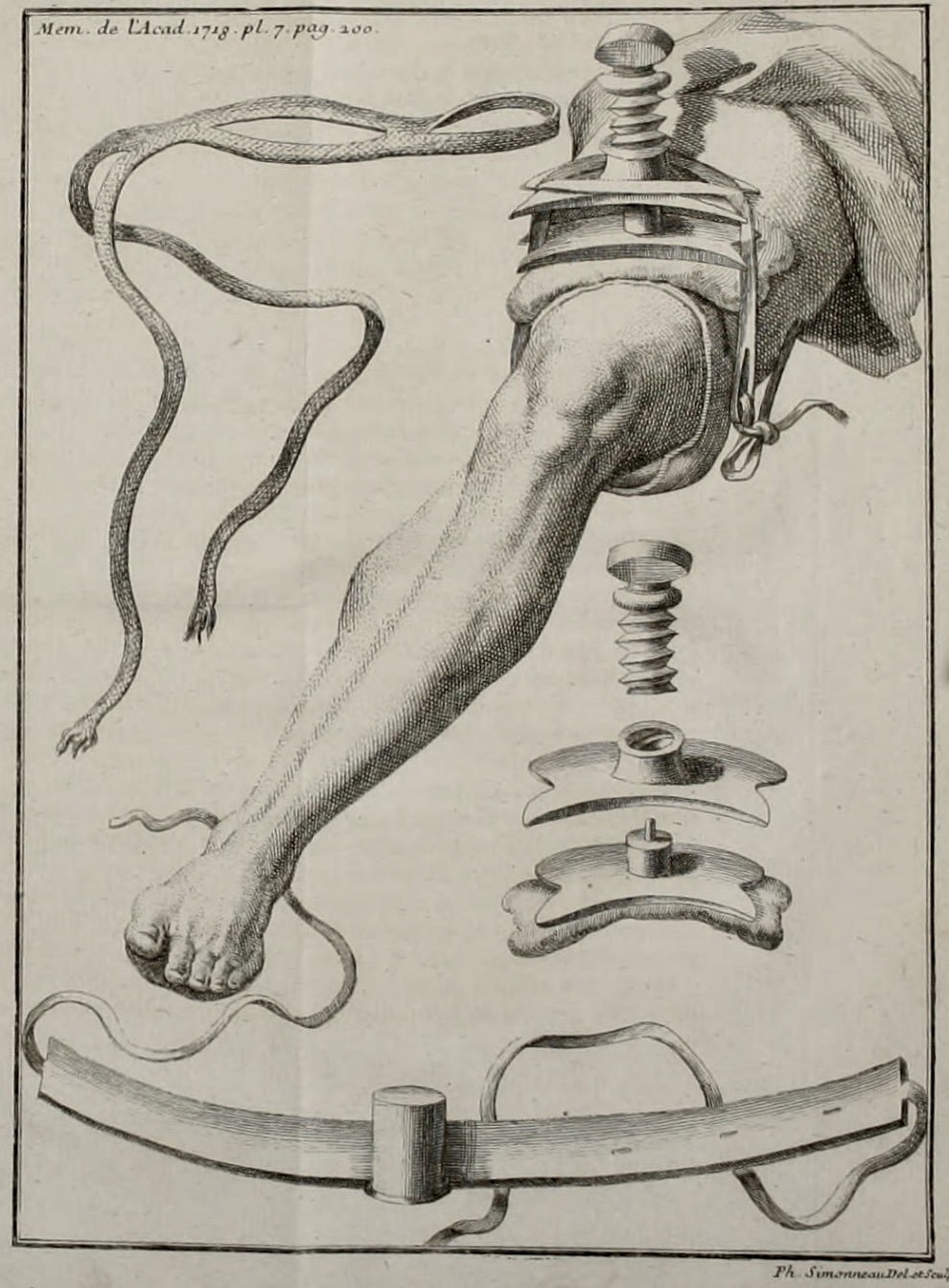

A Spot of History

Tourniquets (from the French verb 'to turn') have been used as far back as 1674, when Morel used one on the battlefield to stem life-threatening limb bleeding during the Siege of Besançon

The first surgeon to regularly use what we would now recognise as an arterial tourniquet was Louis Petit, French surgeon and anatomist from the 17th and 18th centuries.

In 1718 he came up with the following contraption, which neatly combined firm directed pressure over the desired vessels with more gentle, distributed compression over the rest of the limb.

References and Further Reading